Saxo Grammaticus’s Gesta Danorum (c. 1208) and Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (c. 1230) have often been compared. In many regards, these two works are quite similar: both were written during the first half of the thirteenth century and are monumental compilations that retrace the history of the Nordic kingdoms of Denmark and Norway respectively, starting with their legendary pagan pasts, and ending in the twelfth century. Various aspects of these two works have been compared: their prologues (Friis-Jensen 2010), their representations of power (Bagge 2010), their depictions of myths (Clunies Ross 1992), to name but a few. Despite continued interest in comparisons between Saxo’s and Snorri’s works, their respective representations of magic have remained largely unexplored. In this paper, I will compare the two authors’ representations of agents of magic. I will show how beyond their similarities, Saxo’s and Snorri’s magician figures proceed from different conceptions of magic and play markedly different roles in each narrative. To do so, I will start by analyzing Saxo’s and Snorri’s respective vocabulary with regard to magicians and magic. Only then will I describe and compare the actual occurrences of magic and magicians within these respective works.

Saxo’s Typology of Magicians

Both Saxo and Snorri use varied vocabularies to describe the agents of magic and magic in general. The most obvious distinction between their respective vocabularies of magic is the language: Saxo wrote in Latin, while Snorri wrote in Old Norse. As we shall see, the differences between the two authors’ treatment of magic extend further. I will proceed chronologically and first study Saxo’s vocabulary of magic.

The Gesta Danorum is a history of Denmark composed of sixteen books and finished around 1208 by the Danish cleric Saxo Grammaticus for his two patrons, the successive Archbishop of Lund, Absalon († 1201), and Anders Sunesen († 1228). Saxo is the first Scandinavian author to have produced lengthy narratives about the Scandinavian pagan gods. In this regard, he used the theory of euhemerism (Piet 2023). This ancient theory, named after Euhemerus of Messene, a Greek author from the third century BC, postulates that the pagan gods were in fact human impostors. For Saxo, these impostors were not ordinary human beings, but sorcerers who were especially gifted in the art of illusion. In the first book of the Gesta Danorum, Saxo explains the nature and powers of these sorcerers who deceived pagans in ancient times by providing a typology of three distinct kinds:

Quorum summatim opera perstricturus, ne publice existimationi contraria aut ueri fidem excedentia fidenter astruere uidear, nosse opere pretiumc est, triplex quondam mathematicorum genus inauditi generis miracula discretis exercuisse prestigiis.

Horum primi fuere monstruosi generis uiri, quos gigantes antiquitas nominauit, humane magnitudinis habitum eximia corporum granditate uincentes.

Secundi post hos primam physiculandi solertiam obtinentes artem possedere Phitonicam. Quid quantum superioribus habitu cessere corporeo, tantum uiuaci mentis ingenio prestiterunt. Hos inter gigantesque de rerum summa bellis certabatur assiduis, quoad magi uictores giganteum armis genus subigerent sibique non solum regnandi ius, uerumetiam diuinitatis opinionem consciscerent. Horum utrique per summam ludificandorum oculorum peritiam proprios alienosque uultus uariis rerum imaginibus adumbrare callebant illicibusque formis ueros obscurare conspectus.

Tertii uero generis homines ex alterna superiorum copula pullulantes auctorum suorum nature nec corporum magnitudine nec artium exercitio respondebant. His tamen apud delusas prestigiis mentes diuinitatis accessit opinio. (Friis-Jensen 2015: I.5.2-1.5.5) 1

For Saxo, there are three types of agents of magic. All three belong to the broader category of the mathematici (mathematicians, astrologers). The first category is that of the gigantes (giants), while the second is attributed with those who have the physiculandi solertia (competence of haruspices) and possess the ars pythonica (prophetic art). While Saxo represents the giants as being remarkable due to their size, he also notes that they were skilled in disguise and illusion, just like the individuals in the second category. The third category is composed of the first two categories’ offspring, though little is known about them aside from their lack of talent compared to their progenitors. In his edition of Saxo’s text, Karsten Friis-Jensen (2015: I.5.2. note 1) argues that:

Among Saxo’s three classes of gods the two first no doubt reflects the distinction in Scandinavian mythology between Giants and Æsir; the third class cannot be identified, but it may refer to another group that fought with the Æsir, the Vanir.

Indeed, Saxo’s description seems to reflect the opposition between the Old Norse gods and the jǫtnar (giants) to the degree that it is perceptible in eddic poems, as well as in Snorri’s Edda written in the 1220’s. The Old Norse word jǫtunn is often synonymous with “giant,” and Saxo’s second category evidently refers to the Old Norse pagan gods, as he contends that they were thought to be divinities. However, it is unlikely that the third category corresponds with the Vanir. Saxo defines the individuals from the third category as descendants from the first two who lack magical abilities. This description is not in accordance with what is known of the Vanir in Old Norse sources: the Vanir are never designated as the descendants of gods and giants, and they are said to be competent magicians, perhaps even more so than the Æsir.

In fact, there is good reason to believe that Saxo was unfamiliar with the concept of the Vanir. The Gesta Danorum is older than Snorri’s Edda, and as Rudolf Simek (2010: 10-19) argues, one cannot exclude the possibility that the dichotomy between the Æsir and the Vanir is Snorri’s invention, resulting from a 13th-century interpretation of Eddic poetry. If this were true, Saxo’s typology of magicians has little to do with traditional Old Norse partitions of deities between the Æsir, the Vanir, and giants, and one should refrain from applying Snorri’s conceptions of deities in the Edda to Saxo’s text.

In this sense, it is useful to analyze Saxo’s Latin vocabulary and its sources. Mathematicus, gigans, and ars pythonica, are all concepts found in one of the most important encyclopedic works of the Middle Ages, the Etymologies (c. 625) of Isidore of Seville. The ninth chapter of the eighth book of this work is dedicated to magicians (magis), (Canale 2004: VIII.9.21-27). For Isidore, all agents of magic fall within the category of magi, which is also the term that refers to the wise men who offered gifts to the newborn Jesus (Matthew 2) in the Vulgate translation of the Bible. According to Isidore, various subcategories of magic exist within this group. Among them are the Pythonissae who, according to Isidore, were named after Apollo Pythian because he was “the inventor of divination.”

Isidore pursues his account with the Genethliaci, individuals who predict the lives of others based on the twelve signs of heaven and the observation of the stars. These Genethliaci, he states, were once called magi but are now only referred to as mathematici. Hence, for Isidore, the term magus carries two meanings. First, it is employed as an umbrella term to designate any kind of magician, and second, it is used as a synonym for a subcategory of magicians: the mathematicus or “astrologer”. As Jean-Patrice Boudet (2006: 205-206) remarks, the conflation between the mathematici and the magi is a medieval phenomenon that began with Isidore.

We may note that the adjective phythonicus (prophetic), as well as the related terms “python” (seer, or prophetic spirit) and pythonissa (seeress) are also found in the Vulgate translation of the Old Testament in passages that condemn the consultation of seers and magicians. For instance, the Witch of Endor, whom king Saul consulted to communicate with the spirit of the prophet Samuel, is referred to as a pythonissa (1 Chronicle 10:13). As Boudet (2006, 231) notes, in both biblical and medieval tradition, the art of the pythonissa was especially perceived as an invocation of the devil.

As for the word physiculandi, it is not found in the Etymologies. It is an alternative spelling of the genitive gerund form of the verb fissiculo (to divide the entrails of a sacrificial victim). This verb is found twice—with the fissiculo spelling—in De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii [On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury], written circa 410 by Martianus Capella: once in I.9 and again in II.151 (Willis 1983: 6, 46). Contrary to what Saxo’s spelling suggests, this word has no connection with the Greek φύσις (nature) but is cognate with the verb “findere” (to split) and the substantive “fissio” (the act of splitting). In classical Latin, fissiculo refers to the act of dividing the entrails of a sacrificial victim to produce oracles.

The first category of Saxo’s typology of mathematici is clear: the giants are systematically identified as giants within the texts. The second and third categories, however, are not as transparent. According to Saxo, the individuals in the latter two categories were both thought to be divinities. The ones from the second category are said to have waged war against the giants. In this regard, these characters are similar to the Old Norse gods, who often fight against giants in both Snorri’s Edda and in Eddic poetry. Furthermore, as Jonas Wellendorf (2018: 75) notes, Saxo describes the most important of his pseudo-gods, Othinus (Odin), as a soothsayer, which would situate him within the second category. As for Sigurd Kværndrup (1999: 126) and Inge Skovgaard-Petersen (1981: 121), they suggest that several different characters appear under the identity of Othinus. For them, the Othinus from book I is not the same as the Othinus from book IX. Indeed, the events in book I take place before the birth of Christ, while book IX recounts events from the ninth century. However, it is unclear whether the later appearances of Othinus are to be understood as descendants of the first one, as demons, or simply as the same character who would have lived an unnaturally long life. We may nonetheless note that in his Edda, Snorri gave a similar explanation for the longevity of the pseudo-gods within Scandinavian history: for him, the gods from historical times are distant descendants of the original pseudo-gods of the same names who came from Troy (Anthony Faulkes 1982: 4-5).

In summary, Saxo’s typology of the mathematici comprises three types of magicians. Only two of these types are indubitably described as agents of magic: the giants are skilled in the art of disguise, and the pseudo-gods also possess the gift of prophecy in addition to disguise. As we shall see in the following discussion, Saxo’s typology does not actually reflect his depiction of agents of magic within the narratives of the Gesta Danorum. Prior to this, however, I will discuss Snorri’s vocabulary to describe magic.

The Vocabulary of Magic in the Heimskringla

The Heimskringla (c. 1230) is a compilation of sixteen sagas that recounts the history of the Norwegian kings from the dynasty’s legendary origin to the reign of Magnús Erlingsson (1161-1184). Like Saxo, Snorri recounts the pagan past of Scandinavia and describes the pagan pseudo-gods as agents of magic. However, contrary to Saxo, Snorri does not produce a typology of the magician figure, though he nonetheless uses the theory of euhemerism and describes the pagan pseudo-gods as magicians. For Snorri, the pseudo-gods were initially from Asia Minor, and thus were named the Æsir (sing. Áss), a word that Snorri interprets to mean “Asians.” The Æsir later moved to Scandinavia, for they were chased from their country by the Roman Invasions. The first agent of magic introduced by Snorri in the Heimskringla is Óðinn, the leader of the Æsir. This pseudo-god appears in the second chapter of the Ynglinga saga, the first saga of the Heimskringla, which takes place in the legendary pagan past of Scandinavia. Here is one of the first passages where Óðinn practices magic:

Þá tóku þeir Mími ok hálshjoggu ok sendu hǫfuðit Ásum. Óðinn tók hǫfuðit ok smurði urtum þeim, er eigi mátti fúna, ok kvað þar yfir galdra ok magnaði svá, at þat mælti við hann ok sagði honum marga leynda hluti. (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 13)2

Here Snorri uses two words related to magic to describe Óðinn’s action: one substantive, “galdr” (pl. galdrar) and one verb, “magna.” Galdrar refers to magic songs and in this case is used in combination with the verb kveða, which means to say, utter, to recite. As for the verb magna, it signifies to charm or to strengthen by spell. Here, the narrator links Óðinn’s magic to the act of speaking: the pseudo-gods cast spells by uttering formulas aloud in order to make a dead man’s head speak. This association is unsurprising, as Óðinn is widely regarded as a god of poetry who is particularly gifted in poetry and wisdom.

This episode regarding Mímir’s head occurs before the Æsir learn seiðr, another type of magic. Seiðr is introduced later in the same chapter when the Æsir encounter another family of pseudo-gods, the Vanir. Among them is Freyja who, according to the narrator, was the first to teach seiðr to the Æsir: “Dóttir Njarðar var Freyja. Hon var blótgyðja. Honn kenndi fyrst með Ásum seið, sem Vǫnum var títt.”3 In both the Heimskringla and in other texts, we may note that Freyja is a character associated with immoral sexual behaviors, as she used to practice incest, and who is equally described as “fickle” (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a:13, 25). As we shall see, the dangerous sexuality of the agents of magic is a recurring theme in the Heimskringla. The narrator does not immediately explain what seiðr is, but he is more explicit in chapter seven, when he describes Óðinn’s power:

Óðinn skipti hǫmum. Lá þá búkrinn sem sofinn eða dauðr, en hann var þá fugl eða dýr, fiskr eða ormr ok fór á einni svipstund á fjarlæg lǫnd at sínum ørendum eða annara manna. Þat kunni hann enn at gera með orðum einum at sløkkva eld ok kyrra sjá ok snúa vindum hverja leið, er hann vildi, ok hann átti skip, er Skíðblaðnir hét, er hann fór á yfir hǫf stór, en þat mátti vefja saman sem dúk. Óðinn hafði með sér hǫfuð Mímis, ok sagði þat honum mǫrg tíðendi ór ǫðrum heimum, en stundum vakði hann upp dauða menn ór jǫrðu eða draugadróttin eða hangadróttin. Hann átti hrafna tvá, er hann hafði tamit við mal. Flugu þeir víða um lǫnd ok sǫgðu honum mǫrg tíðendi. Af þessum hlutum varð hann stórliga fróðr. Allar þessar íþróttir kenndi han með rúnum ok ljóðum þeim, er galdrar heita. Fyrir því eru Æsir kallaðir galdrasmiðir. Óðinn kunni þá íþrótt, svá at mestr máttr fylgði, ok framði sjálfr, er seiðr heitir, en af því mátti hann vita ørlǫg manna ok óorðna hluti, svá ok at gera mǫnnum bana eða óhamingju eða vanheilendi, svá ok at taka frá mǫnnum vit eða afl ok gefa ǫðrum. En þessi fjǫlkynngi, er framið er, fylgir svá mikil ergi, at eigi þótti karlmǫmum skammlaust við at fara, ok var gyðjunum kennd sú íþrótt. Óðinn vissi um allt jarðfé, hvar fólgit var, ok hann kunni þau ljóð, er upp lauksk fyrir honum jǫrðin ok bjǫrg ok steinar ok hraugarnir, ok batt hann með orðum einum þá, er fyrir bjoggu, ok gekk inn ok tók þar slíkt er hann vildi. Af þessum krǫptum varð hann mjǫk frægr.4 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 18-19)

As is evident from this description, Snorri’s version of Óðinn possesses more powers than that of Saxo, and Snorri uses a broader vocabulary to describe his magical abilities. Like Saxo’s Othinus, Óðinn is a soothsayer, a power that the narrator connects with seiðr, which, according to him, is a practice traditionally reserved for women and seen as inappropriate or perverse for men. As Nicolas Meylan (2014: 42-43) notes, this judgement is not unique to Snorri, and seiðr is a practice widely regarded as both immoral and powerful within the Old Norse corpus. The idea that Óðinn, the chief among the Nordic gods, practices a form of magic that renders him unmanly has been the subject of numerous interpretations. Ármann Jakobsson (2011: 13) commented that “A god who is queer is not queer.” We may note that in Ynglinga saga, Óðinn is not a god but a king and a cultural hero, though Ármann is certainly right to remark that the figure of Óðinn appears to be more than human. As I will discuss in part IV, Óðinn is not the only figure of authority who breaks social rules.

In this passage, the narrator refers to seiðr as being fjǫlkynngi (sorcery). As such, Snorri does not produce an explicit typology of magicians as Saxo did, but he implicitly describes seiðr as a subcategory within the broader category of fjǫlkynngi. However, this categorization of magic is implicit and appears to be of little importance to the author. The narrator’s main preoccupation when describing magic becomes clearer at the end of his description of Óðinn, which is in the same chapter as his description of how Óðinn passed his knowledge of magic on to his followers:

En hann kenndi flestar íþróttir sínar blótgoðunum. Váru þeir næst honum um allan fróðleik ok fjǫlkynngi. Margir aðrir námu þó mikit af, ok hefir þaðan af dreifzk fjǫlkynngin víða ok haldizk lengi. En Óðin ok þá hǫfðingja tólf blótuðu mennn ok kǫlluðu goð sín ok trúðu á lengi síðan.5 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 19-20)

In fact, the Heimskringla is not as much about defining seiðr and fjǫlkynngi as it is about explaining the story of their transmission and their impact on society. In the Heimskringla, Snorri describes an unbroken chain of transmission for the knowledge of seiðr. According to Snorri, seiðr first became known via Freyja and was then taught to Óðinn, who subsequently passed his knowledge on to his priests. In doing so, Snorri develops the idea that fjǫlkynngi, seiðr, and paganism are intimately connected. As we shall see, this idea is an essential aspect of the author’s conception of magic throughout the Heimskringla.

As is evident from the previous discussion, both Saxo and Snorri introduce the concept of magic early on in their respective works. Both authors use varied vocabularies to describe magic and to associate it with the pseudo-gods of pre-Christian Scandinavia. Nonetheless, we can already observe significant differences between their respective treatment of the agents of magic. Saxo’s mathematici are experts in illusion and use their power to pass as gods, for the mathematici deluded human minds. In contrast, the narrator of the Heimskringla never depicts Óðinn as using his magical abilities to deceive humans into worshiping him as a god. Instead, he willingly shares his knowledge of magic with his priests.

This distinction between the pseudo-gods of Saxo, who keep their knowledge of the magical arts for themselves, and the pseudo-gods of Snorri, who share their knowledge with others, is reminiscent of, though not identical to, the distinction made between “witches” and “sorcerers,” as conceptualized by Africanists. Witches refer to those agents of magic who inherited their power from birth, while sorcerers are individuals who have learned this art. Stephen Mitchell (2003: 132-141) applies these anthropological conceptions to the Old Norse sagas and notes that the Old Norse agents of magic often acquire their power by learning. In the case of the Ynglinga saga, Snorri puts great emphasis on the acts of teaching and learning magic. One consequence of this emphasis is that most of the agents of magic in the Heimskringla are not the pseudo-gods themselves but ordinary beings who learned magic, either by way of the pseudo-gods or from another source. On the contrary, Saxo speaks very little about the acquisition of magic power, and his agents of magic appear to have been born magicians. Consequently, almost all agents of magic in the Gesta Danorum are either giants or pseudo-gods rather than ordinary human beings.

Conjurors of Cheap Tricks: Agents of Magic in the Gesta Danorum

The first agents of magic that Saxo describes in his typology of mathematici are the giants. These beings are also the first magicians to appear in the Gesta Danorum, in which they are represented as antagonists to the Danish heroes of ancient times. Not all giants in the Gesta Danorum act as agents of magic. In the first book, Saxo recounts the life of the legendary Danish hero, Gram. As recounted in I.4.2-I.4.10, the Swedish king, Sigtrygg, wishes to marry off his daughter, Gro, to a giant. Gram is revolted by this idea and refers to such a union as: “indignam regio sanguine copulam”6 (Friis-Jensen 2015: 1.4.2). To save the princess, Gram impersonates a giant. Unaware that her savior is actually a man and not a giant, Gro laments about her condition and utters the following stanza:

Que sensus exors scortum uelit esse gigantum

Aut que monstriferum possit amare thorum?7 (Friis-Jensen 2015: 1.4.9)

Surprisingly, Gram has entrusted a giant, Vagnhofth, to protect and raise his own son, Hadingus, who is one of the most important characters in book I.8 Later, Vagnhofth’s daughter, Harthgrepa, who is also Hadingus’ wet nurse, as well as his foster sister, tries to seduce the young hero. Hadingus, who is initially unconvinced by the proposal, remarks that the difference in size between the two of them is too important:

Quo corporis eius magnitudinem humanis inhabilem amplexibus referente, cuius nature contextum dubium non esset giganteo germini respondere: ‘Non te moueat’, inquit, ‘insolitus mee granditatis aspectus. Nunc enim contractioris, nunc capacioris, nunc exilis, nunc aflluentis substantie, modo corrugati, modo explicati corporis situm arbitraria mutatione transformo. Nunc proceritate celis inuehor, nunc in hominem angustioris habitus ditionec componor.’9 (Friis-Jensen 2015: I.6.3)

Ultimately, the giantess convinces the hero with a poem that ends with the following words: “maiore feroces territo, concubitus hominum breuiore capesso”10 (Friis-Jensen 2015: 1.6.3). Shortly after, in I.6.4, Harthgrepa convinces Hadingus to invoke the spirit of a deceased man in order to consult the will of the gods. As soon as he rises from the dead, the spirit starts to curse Harthgrepa, who dies soon after, in I.6.5-6. This episode is reminiscent of the biblical narrative about the Witch of Endor recounted in 1 Samuel 28:3-25, in which the dethroned King Saul asks a woman to invoke a python (a prophetic spirit), who in this case is the spirit of the deceased prophet Samuel and whom Saul wishes to consult for advice. As in the case of Harthgrepa, the spirit fails to help Saul but immediately curses him. In this episode, Harthgrepa is implicitly but quite clearly described as practicing ars pythonica (prophetic art), an activity which, according to Saxo’s own typology of magician, falls within the domain of the pseudo-gods rather than of the giants.

Despite having been seduced by a giantess himself, Hadingus, like his father, saves a princess, this time Regnhild, from being married to a giant. Once again, the narrator portrays the union negatively (Friis-Jensen 2015: I.8.13). Finally, the last giants of the Gesta Danorum appear in book VIII, during King Gorm and the Icelander Thorkill’s expeditions to the land of the giant Geirrøth in the far north. There, the adventurers meet Guthmund, Geirrøth’s brother, who attempts to undermine his hosts’ chastity by offering his daughter and her handmaidens to King Gorm and his crewmen (Friis-Jensen 2015: VIII.14.10).

As we may observe in the Gesta Danorum, giants are consistently characterized as taking part in unlawful relationships. Their victims may be both male and female humans. Males, such as Hadingus and Gorm’s crewmen, are seduced by giantesses, while females, such as Gro and Regnhild, are abducted against their will. As made evident by Gro’s complaints, the author abhors the mere idea of a union between a female human and a giant. Saxo does not explicitly express such negative views on the union between a male human and a giantess, but he nonetheless describes such relationships as abnormal: the relationship between Hadingus and Harthgrepa, his wet nurse and foster sister, is almost incestuous, and the giant Guthmund uses his daughter to destroy the virtue of King Gorm. In short, while giants are abductors, the giantesses are dangerous temptresses.

The second type of agents of magic in the Gesta Danorum is comprised of the pseudo-gods. As was also the case for the giants, the pseudo-gods are not systematically portrayed as magicians. It is likely, though uncertain, that Othinus’ first appearance in the Gesta Danorum occurs in I.6.7, when the narrator describes how an anonymous one-eyed individual aids the hero Hadingus.11 The narrator describes this character as an agent of magic who utters a prophecy, carries Hadingus on his horse across the sea, and gives him a potion to bolster his health and strength (Friis-Jensen 2015: I.6.7-9).

Throughout the Gesta Danorum, Othinus reappears several times in similar situations, where he seemingly acts as the friend of Danish heroes. In VII.10.3, the pseudo-god confers the gift of invulnerability on Harald Hilditan in exchange for the souls of the men Harald will kill in battle. Surprisingly, in VIII.4.9, the pseudo-god disguises himself as one of Harald’s advisors and kills the king for no apparent reason. Later, in IX.4.12, Othinus appears under the alias Rostarus and heals the hero Sigvard, again in exchange for the souls of the men the hero will kill. Just like in Snorri’s Edda (Faulkes 2005: 21), Othinus collects the souls of dead warriors. However, there is no indication here that Othinus does so in preparation for Ragnarok. Instead, Othinus’ proposal to gift earthly goods in exchange for souls is reminiscent of the motif of the pact with the devil.12

In these episodes, Othinus appears to be a relatively powerful character, though this is not always the case. One of the most important episodes involving Othinus in the Gesta Danorum portrays his failed attempt to woo the Ruthenian (Russian) princess Rinda in book III (Friis-Jensen 2015: III.4.1-8). In this episode, Othinus seeks to avenge his son Balderus who died earlier in book III (Friis-Jensen 2015: III.3.7). For this reason, the pseudo-gods consult a seer who foretells that Othinus will beget a son with the Ruthenian princess Rinda, and that this son will avenge Balderus. The narrator ironically comments that:

At Othinus, quamquam deorum precipuus haberetur, diuinos tamen et aruspices ceterosque, quos exquisitis prescientie studiis uigere compererat, super exequenda filii ultione sollicitat. Plerunque enim humane opis indiga est imperfecta diuinitas.13 (Friis-Jensen 2015: III.4.1)

To fulfill the seer’s prophecy, Othinus infiltrates the Ruthenian king’s court by posing as a soldier, ultimately earning the king’s trust and rising to the status of a high-ranking general and confidant. As the narrator states, Othinus’ subterfuges are not merely a disguise but instead stem from his magical abilities: “Ita prestigiarum peritis uersili uultu uarios habitus pre se fe rendi promptissima quondam potestas incesserat. Quippe preter naturalem corporis speciem cuiuslibet etatis statum simulare callebant”14 (Friis-Jensen 2015: III.4.4). Despite these efforts, however, Othinus fails to win Rinda’s affection, which leads to a series of rejections. In a desperate effort after all his disguises have proven futile, Othinus resorts to using a tree bark inscribed with formulas (Friis-Jensen 2015: III.4.4) to cast a spell on Rinda, which makes her ill. Disguised as a female physician, Othinus subsequently rapes the princess. Othinus thus fulfills the prophecy, but the other pseudo-gods deem his actions so dishonorable that they banish him and replace him with Ollerus (Friis-Jensen 2015: III.4.12). As we have observed, Saxo’s depiction of Othinus contradicts his own typology of the mathematici, according to which the pseudo-gods are competent soothsayers. In effect, Saxo’s only reference to soothsaying with regard to Othinus is to underscore Othinus’ lack of skills in this domain.

In summary, in the Gesta Danorum, the two main groups of agents of magic are the giants and the pseudo-gods, among whom Othinus plays the principal role. The giants are indeed shapeshifters, as can be seen in the episode where Harthgrepa seduces Hadingus, but they may also embody the role of soothsayers. On the contrary, Othinus is not a soothsayer but a master of disguise who regularly hides his identity. His reasons for doing so may vary: it may be a means to trick heroes into offering him the souls of dead warriors, or to betray and kill them. The lengthiest narrative about him practicing magic is the one in which he courts Rinda, and none of his disguises work as intended. Most notably, nearly all of Saxo’s mathematici are predatory toward the opposite gender: giants are abductors, giantesses are seductresses, and Othinus is a rapist. As we shall see, magic in the Heimskringla is, among other things, connected to sexuality.

The Rebels and the Finnar: Agents of Magic in the Heimskringla

As we saw in the Heimskringla, the pseudo-gods are the originators of magic within Nordic society. However, contrary to the Gesta Danorum, in the Heimskringla, the pseudo-gods teach their arts, and ordinary humans continue to practice magic after them. As I will now argue, the narrator of the Heimskringla consistently describes sorcery as a tool used by the powerless, the wronged, the rebels, and, more generally, by those who cannot or do not wish to employ more honorable or legitimate means of defending themselves, be it through violence or legal procedures.

This notion, that magic is the weapon of the weak, is not unique to the Heimskringla and is also found in the Íslendigasögur (sagas of the Icelanders). As Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir remarks, magic is one of the weapons used by women in the Íslendigasögur to attain their objectives (Friðriksdóttir 2009: 425). As one of the tools available to the vulnerable and the powerless, magic is also understandably depicted as a vector of social troubles. This characterization of magic as a means of causing disorder is explicitly expressed in chapter 14 of Ynglinga saga. This chapter recounts how King Vísburr and his first wife sired two sons, who the king then repudiates. The two disinherited sons later return to their father to claim their rightful part of their inheritance, but Vísburr refuses. In retaliation, the two sons curse their father and hire a sorceress to cast a spell on their behalf:

Þá var enn fengit at seið ok siðit til þess, at þeir skyldi mega drepa fǫður sinn. Þá sagði Hulð vǫlva þeim, at hon myndi svá síða ok þat með, at ættvíg skyldi ávallt vera í ætt þeira Ynglinga síðan. Þeir játtu því. Eptir þat sǫmnuðu þeir liði ok kómu at Vísbur um nótt á óvart ok brenndu hann inni.15 (Aðalbarnarson 2002a: 30)

In this episode, the wronged sons of Vísburr use witchcraft to pursue their reasonable claim to the inheritance that the king wrongfully refuses them. Here, the narrator acknowledges the unlawful behavior of the powerful and the mistreatment of the powerless. Yet, this does not indicate that the narrator sides with the rebels. In fact, the narrator depicts rebellion, and the use of magic, as dangerous and harmful actions: the two sons agree to curse their own family line for eternity, a decision that proves disastrous for later generations.

In short, the narrator does not encourage rebellion but acknowledges the responsibility of bad rulers in the occurrence of rebellions. In this narrative, the poor management of one’s inheritance is the main cause of family strife, a subject which remains one of the main themes in the Heimskringla, as well as in the later sagas of the compilation. The thirteenth saga of the compilation, Magnúss saga blinda ok Haralds gilla, is largely about the events that led to the beginning of the civil war. According to Snorri’s depiction of these events, King Sigurðr jórsalafari († 1130) attempted to convince his people to accept his son Magnús († 1139) as his successor instead of another potential heir, Sigurðr’s half-brother, Haraldr gilli († 1136) (Aðalbjarnarson 2012: 266, 278). Initially, the two heirs had ruled conjointly, but the civil war (1130-1240) began when Magnús tried to seize power and waged war against Haraldr gilli’s. In this perspective, the episode of Hulð’s malediction acts as an intradiegetic explanation for the pervasive practice of parricide and family strife in later Norwegian history, and magic is represented as the vector of social disorders, as well as a historical force that bridges Norway’s past and present.

The association between sorcery, family strife, parricide, and rebellion is found again in two other sagas from the Heimskringla: Haralds saga hárfagra and Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, the third and sixth sagas of the compilation, respectively. Haralds saga hárfagra contains a narrative in which the narrator explains how the Finnar (Saamis) introduced the practice of sorcery within the family of King Haraldr. According to this saga, King Haraldr, the first king to unify Norway, married the princess Snæfríðr Svásadóttir, the daughter of a Finnr king. The narrator recounts her encounter with Haraldr:

Þar stóð upp Snæfríðr, dóttir Svása, kvinna fríðustm ok byrlaði konungi ker fullt mjaðar, en hann tók allt saman ok hǫnd hennar, ok þegar var sem eldshiti kvæmi í hǫrund hans ok vildi þegar hafa hana á þeiri nótt. En Svási sagði, at þat myndi eigi vera nema at honum nauðgum, nema konungr festi hana ok fengi at lǫgum, en konungr festi Snæfríði ok fekk ok unni svá með œrslum, at ríki sitt ok allt þat, er honum byrjaði, þá fyrir lét hann.16 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 125-126)

The narrator implicitly describes the source of Snæfríðr’s appeal as supernatural: mere contact with the king’s hand was enough to seduce him immediately. It is certainly significant that Snæfríðr’s magic worked by touching the king. Just as the eloquent Óðinn from Ynglinga saga used speech-related magic, so the magic of Snæfríðr, a seductress, functions by way of sensual means. Haraldr’s attraction toward Snæfríðr is unhealthy and destructive, as it causes him to neglect his kingly duties. Snæfríðr’s demonic nature is made clear after her death, when several critters swarm from her decaying body: “Blánaði áðr allr líkaminn, ok ullu ór ormar ok eðlur, froskar ok pǫddur ok alls kyns illyrmi.”17 Significantly, in Óláfs saga helga, the seventh saga of the compilation, the same animals are said to escape from the idol of the god Þórr which Saint Óláfr destroyed (Aðalbjarnarson 2002b: 189). This parallel reinforces an idea that had already been introduced in the Ynglinga saga, that sorcery and paganism are closely connected and are two aspects of the same demonic influence on orderly society.

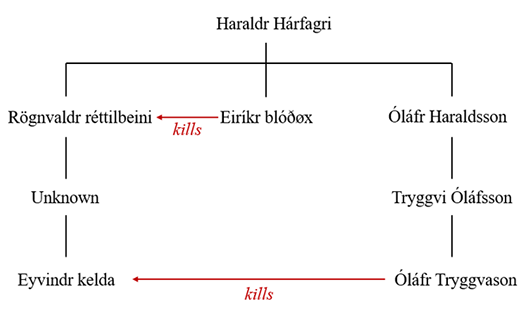

The harmful influence of Snæfríðr on Norwegian society persists after her death: one of her children with Haraldr is Rǫgnvaldr réttilbeini who, in chapter 34 of the same saga, becomes a seiðmaðr (a man who practices seiðr, or a sorcerer.) King Haraldr, who abhors sorcerers, sends his other son, Eiríkr Blóðǫx, to kill Rǫgnvaldr, and thus effectively commits parricide (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 139). We may note that although parricide is considered a grave crime in Old Norse society, the narrator of the Heimskringla describes Eiríks action as deserving of praise: “Var þat verk lofat mjǫk.18” This indicates that Rǫgnvaldr’s transgression was severe enough to justify making an exception with regard to the prohibition of parricide. The union between Haraldr and Snæfríðr effectively leads to an enduring division within the line of Haraldr hárfagri. In Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, King Óláfr Tryggvason, the great grandson of Haraldr hárfagri, fights and kills another magician, Eyvindr Kelda, who is himself the great grandson of Haraldr through Rǫgnvaldr. See figure below:

Fig. 1: Family strife within the line of Haraldr hárfagri

As such, Snæfríðr, introduced magic into the family of the Norwegian kings, just as Freyja introduced magic into the society of the Æsir. In this regard, the Finnar play the same role in historical times as the Vanir in mythological times. In fact, for Snorri, the Finnar do not only introduce sorcery into Norwegian society through intermarriage but also by transmitting their knowledge to the Norwegian people. For instance, this is the case in chapter thirty-two of Haralds saga hárfagra for Gunnhildr, Mother of Kings, who explains that she has come to the land of the Finnar to learn kunnasta (magical lore) (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 135). It is significant that Saxo, who also mentions this same character and describes her as an agent of magic, never indicates that she has any relation with the Finnar (Friis-Jensen 2015: X.1.7).

Throughout the Heimskringla, the Finnar are continually associated with magic (Price 2019, 191-196). One of the most notable episodes that shows their connection with sorcery is found in chapter 76 of Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar and recounts how King Óláfr Tryggvason chased and captured another magician who is also named Eyvindr, Eyvindr Kinnrifa. This is Snorri’s account of the meeting between Evyndr and Óláfr:

Var þá Eyvindr fluttr til tals við Óláf konung. Bauð konungr honum at taka skírn sem ǫðrum mǫnnum. Eyvindr kvað þar nei við. Konungr bað hann blíðum orðum at taka við kristni ok segir honum marga skynsemi ok svá byskup. Eyvindr skipaðisk ekki við þat. Þá bauð konungr honum gjafar ok veizlur stórar, en Eyvindr neitti ǫllu því. Þá hét konungr honum meizlum eða dauða. Ekki skipaðisk Eyvindr við þat. Síðan lét konongr bera inn munnlaug fulla af glóðum ok steja á kvið Eyvindr: „Taki af mér munnlaugina. Ek vil mæla orð nǫkkur, áðr ek dey.“ Ok var svá gǫrt. Þá spurði konungr: „Viltu nú, Eyvindr, Trúa á Krist?“ „Nei,“, segir hann, „ek má enga skírn fá. Ek em einn andi, kviknaðr í mannslíkam með fjǫlkynngi Finna, en faðir minn ok móðir fengu áðr ekki barn átt.“ Síðan dó Eyvindr ok hafði verit inn fjǫlkunngasti maðr.19 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002a: 323)

This narrative is reminiscent of Christian stories in which martyrs who are tortured at the hands of pagan rulers nonetheless maintain their faith. In this perspective, Magnús Fjalldal (2013: 465-468) reads this episode as a criticism of the king’s abuse. However, there are several arguments that go against such a view. At a first glance, the author seems to cast king Óláfr as a cruel ruler: Eyvindr, who is the incarnation of a woman-born demon, is evidently designed to be the reverse image of Christ, or a literal antichrist. In this regard, Óláfr is not only similar to pagan rulers who oppressed Christian saints, but his role in the narrative also mirrors that of Satan, who tempted Christ with gifts in the desert (Matthew 4:1–11, Mark 1:12–13, Luke 4:1–13). Like Satan, Óláfr first offers gifts and then tortures his victim, and he is cast as both a tempter and a persecutor. This characterization is unsettling and raises questions about why the author would draw parallels between his Christian hero and negative figures such as pagan persecutors or Satan himself. The main difference between this particular narrative and traditional stories about Christian martyrs is the reason for which the persecuted character fails to relinquish his faith. In hagiographies, Christian martyrs are able to renounce their religion, but they do not do so, owing to their willpower and the strength of their faith. In the case of this saga, Eyvindr’s resistance is not due to his strength but due to his identity as a demon, for he cannot be baptized. As he says himself: “ek má enga skírn fá.”20 In this manner, the narrator of the Heimskringla casts sorcerers as rebels with whom negotiation is impossible, as they do not even have the freewill necessary to willingly submit to the king’s authority. In this sense, Óláfr’s actions are not gratuitous acts of cruelty but instead last resort measures against unruly subjects who cannot be subdued otherwise. Far from a criticism of the king’s harshness, this narrative justifies his violence and characterizes it as unpleasant yet necessary.

Finally, the last important narratives that involve magic, the Finnar and rebellion, take place in Óláfs saga helga, which recounts the deeds of Saint Óláfr Haraldsson, the patron saint of Norway and arguably the most important character in the Heimskringla. One of King Óláfr’s opponents is Þórir hundr (dog), a Norwegian man with close relations to the Finnar and who purchased from them twelve reindeer-skin coats. The narrator states that these coats were made by using magic: “Hann lét þar gera sér tólf hreinbjálba með svá mikill fjǫlkynngi, at ekki vápn festi á ok síðr miklu en á hringabrynju”21 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002b: 345). Þórir uses one of these coats at the Battle of Stiklestad (1030). This battle, in which King Óláfr opposes Norwegian farmers, is recounted from chapter 219 to chapter 229 in Óláfs saga helga.

It is because of his magical protection that Þórir is unharmed by Saint Óláfr’s sword blow in chapter 228 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002b: 382), thus allowing him to strike Óláfr with his spear soon after:

Þorsteinn knarrasmiðr hjó til Óláfs konungs með øxi, ok kom þat hǫgg á fótinn vinstra við knéit fyrir ofan. Finnr Árnason drap þegar Þorstein. En við sár þat hneigðisk konungr upp við stein einn ok kastaði sverðinu ok bað sér guð hjálpa. Þá lagði Þórir hundr spjóti til hans. Kom lagit neðam undi brynjuna ok renndi upp í kvíðinn.22 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002b: 385)

The narrator designed the narrative of Óláfr’s death to imitate the passion of Christ, and Þórir plays an important role in this scene. Like Christ on the cross who cried, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34, Matthew 27:46), Óláfr also calls for God’s help: “[Hann] bað sér guð hjálpa.” ([He] prayed for God’s help.) It is at this moment that the king is at his most vulnerable and Þórir kills him. The narrator offers a detailed description of the scene, and he depicts Þórir piercing the king’s belly from below. The strike from below is reminiscent of the way in which the Roman soldier pierces Christ’s side in John 19:34, but the similarities between Þórir and the legionary go further. In Matthew and Mark, immediately after Jesus’ death, the soldier claims that “surely this man was the son of God” (Matthew 27:54, Mark 15:38), making him the first human character to explicitly recognize Christ’s divinity in these gospels. In chapter 30 of Heimskringla, Þórir hundr is the first individual to recognize the holiness of Saint Óláfr after his wounds are miraculously healed by the saint king’s blood. As the narrator states:

Váttaði Þórir sjálfr þenna atburð, þá er helgi Óláfs konungs kom upp, fyrir alþýðu. Varð Þórir hundr fyrst til þess at halda upp helgi konungsins þeira ríkismanna, er þar hǫfðu verit í mótstǫðuflokki hans.23 (Aðalbjarnarson 2002b: 387)

The author’s focus on Þórir’s role in spreading the news of Óláfr’s holiness may be intended to mirror the events specifically narrated in the Gospel of John. In John 19:34, the soldier pierces the side of Jesus, and blood and water flow from the wound. In John 19:35, with regard to this miracle, the narrator asserts: “The man who saw it has given testimony, and his testimony is true. He knows that he tells the truth, and he testifies so that you also may believe.”

The narrative about Saint Óláfr’s death illustrates the respective roles of two types of supernatural phenomena: magic challenges royal authority, while miracles reinforce it. Moreover, this narrative also provides a reenactment of the Passion with medieval Norwegian characters. In this play, Saint Óláfr plays the role of Christ, and Þórir that of the Roman soldier. One may wonder whether the Finnar play a role in this story. In fact, the Finnar do not take part in these events per se, for they were not even aware that the coats they sold to Þórir would help him kill the saint. However, I argue that the narrator portrayed the Finnar using medieval anti-judaic tropes, in particular the notion that Jews as a people are responsible for the death of Christ. Richard Cole (2017: 248-253) argues that Snorri’s depiction of Loki’s responsibility in Baldr’s death in the Edda could have been partly modeled on the medieval anti-Judaic perception of the Jews’ role in the death of Christ. Scholars such as Arthur Mosher (1983: 313-14) contend that Loki played the role of Satan, while Hǫðr was modelled on the blind Jewish people who were manipulated by demonic forces. This second interpretation is certainly supported by the common medieval anti-Judaic representation of the Jews as a symbolically blind people who could not see the divinity of Christ. However, as Cole remarks (2017: 248-249), Snorri’s narrative is not a roman à clef in which every character is a pure representation of a real person or group. Instead, Loki is likely a multilayered character, and I agree with Cole when he acknowledges how Loki displays similarities with medieval representations of the Jews. This interpretation of Loki as being somewhat inspired by the figure of the Jewish authorities, is further supported by its structural similarity with the biblical narrative that describes the Jewish authorities as the instigators of Christ’s murder, while the Romans were the ones who carried out the execution. According to this reading, Hǫðr is not modeled after the Jews, but after the Roman soldier, who, like Hǫðr, pierced an innocent divinity.

We may apply a similar reading to the death of Saint Óláfr. In this case, Óláfr is most like Christ, Þórir like the Roman soldier, and the role of the Jews appears to fall on the Finnar. Like Loki in the case of Baldr’s death, the Finnar are the ones who provide the magical tool that helps kill the saintly figure. To be sure, this parallel only works to a certain extent. Unlike Loki or the Jewish authorities in the gospels, the Finnar did not incite anyone to kill Óláfr. However, throughout the Heimskringla, they endorse roles that are reminiscent of the social positions of European Jews in Christian kingdoms. Cole (2017: 248-253) notes: “Like the Jew amongst Christians, Loki is an ethnic Other, because his father Fárbauti belongs to the race of the jǫtnar (giants).” Similarly, in Norwegian Christian society, the Finnar are also seen as outsiders. In this sense, it is possible that saga authors like Snorri chose to portray the Finnar as dangerous sorcerers not only because they were pagans, but also because the authors were influenced, perhaps unconsciously, by Christian anti-Judaic tropes according to which the Jews had a special relation with the devil.24

Conclusion: Danish Witches and Norwegian Sorcerers

Saxo’s and Snorri’s depictions of the agents of magic display certain similarities: both authors describe Othinus, or Óðinn, as an arch-magician, and they both viewed the agents of magic as generally threatening figures. Both Saxo and Snorri also portray magicians as behaving in a predatory manner toward the opposite sex, or as engaging in immoral sexual behaviors. But beyond these similarities, Saxo’s and Snorri’s agents of magic play markedly different roles in their respective works. Saxo’s mathematici never attempt to infiltrate Danish society in the long-term but only to occasionally take advantage of it. They never teach their art, nor do they produce enduring lines of descent with Danish individuals. Consequently, Saxo’s agents of magic remain foreigners who threaten Danish society from the outside. For this reason, their role in Danish history is limited, and they only serve as antagonists in the first books of the work. In doing so, Saxo crafts an image of Denmark’s antiquity according to which the Danes were never fully subjugated by the pseudo-gods and paganism remained a foreign threat.

On the contrary, the insidious agents of magic in the Heimskringla undermine orderly society from the inside and with long-term consequences. Their influence depends on their ability to intermingle with Norwegians or teach their knowledge to the Norwegian people. Throughout the Heimskringla, both magicians and magic are characterized as threats to the family structure and, by extension, to all forms of social hierarchy. This threat is so grave that it calls for extreme measures: when fighting magicians, a man may kill his own brother on his father’s command, and a king may torture his subjects in the most gruesome of manners. In essence, in the Heimskringla, agents of magic can only prosper when the kings fail in their duties, and they can only be eliminated when the kings reassert their authority, often with more brutality than before. In this sense, agents of magic in the Heimskringla play an important role in the author’s wider discourse on the nature of royal power and its limitations.

In summary, while some of Saxo’s agents of magic, such as Othinus, are important characters in the Gesta Danorum, Saxo does not produce a consistent discourse on magic and magicians, and sorcery can hardly be considered an important theme in the Gesta Danorum. In comparison, Snorri’s Óðinn is less important in the Heimskringla than Othinus is in the Gesta Danorum, and most of the work’s other agents of magic are relatively minor characters. Despite the relative unimportance of magician figures, however, Snorri renders magic (and magicians) one of the central themes in the first half of the Heimskringla.