In 2016, the film Sami blood, directed by Amanda Kernell, was released and can be regarded as one of the milestones of regained Sámi awareness. The film was awarded several prizes and praised for its counter-image of the Sámi people. Kernell, who has a Sámi father and Swedish mother, wanted to present the generally negative image of the Sámi in Sweden in the 1930s. The film, told as a frame story, starts when the protagonist Elle Marja has become a 78-year-old woman who calls herself Christina. In the prelude, when Christina travels to Sápmi for the funeral of her sister with her son and granddaughter, a more nuanced picture is given. Her son and granddaughter want to know more about the Sámi, but Christina is very reluctant and even pretends that she cannot speak Sámi. At the end of the film, Christina/Elle Marja seems to embrace her lost and denied identity after she has paid her respects to her sister, whom she had never seen after she fled to Uppsala. After the prelude, the story of young Elle Marja begins. She is an ambitious Sámi girl who wants to become a teacher. However, her Swedish schoolteacher says that she cannot become one because the brains of Sámi people are not apt to it. Elle Marja runs away from her family to Uppsala to fulfil her dream. The film demonstrates the painful process of the forced denial of her Sámi identity in order to archive her goal. In the film, Sápmi, which is the Sámi territory in northern Scandinavia, functions as a biotope for Sámi identity. Outside Sápmi, internal colonization and destruction of identity are taking over. Thus, in Sami blood, there is no cultural hybridity in the sense of a space of in-betweenness, a “third space,” to choose an identity and accept cultural differences (Bhabha, 1994). Elle Marja has to choose between being isolated (a Sámi shall be a Sámi) or assimilated (being like the Swedes). Furthermore, the film contains clear references to scientific racism (biological racism).

Sami blood inspired many artists and authors of Sámi descent. Axelsson’s, Labba’s and Jonsson’s works contain references to Sámi blood and scientific racism. Why is the uprootedness, as depicted in Sami blood, so strong and persistent? Can this trauma be put against the background of colonization and forced migration?

The Sámi

The Sápmi territory in northern Scandinavia was colonized by Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia (the Kola peninsula). 20,000 to 40,000 Sámi live in Sweden, 50,000 to 65,000 in Norway, about 8,000 in Finland, and 2,000 in Russia. It is difficult to give the exact number of Sámi. Sweden, for example, does not collect statistics on the basis of ethnicity or religion. Nine Sámi languages are still spoken to some extent: South Sami, Ume Sami, Pite Sami, Lule Sami, North Sami, Enare Sami, Skolte Sami, Kildin Sami, and Ter Sami.1 Ancestry and family are important. Religion, artistic oral rituals and music (e.g. joik), and language, which are also essential to the Sámi identity, were gradually forbidden in the colonization process.2

The Sámi can be divided into different groups: Reindeer herding and Mountain Sámi, Fishing Sámi, and Forest Sámi. This division refers to the Sámi groups living on the Swedish side (of Sápmi). Besides these four groups, other groups can be added. The first group are the Migrant Sámi, who migrated to the South for work and education. Elle Marja in Sami blood is a good example. The second group are the Lost Sámi, who lost their identity due to Swedish politics. Many members were even denied their past and roots. Sami blood and Mats Jonsson’s comic novel demonstrate this process. The third group are the New Sámi, who rediscovered their Sámi roots. The protagonist of Jonsson’s När vi var samer represents the painful discovery of the lost identity and also tries to understand the denial of the Sámi identity by his grandfather. The fourth and last group are the Sámi fans, persons who are not Sámi themselves but strongly identify with Sámi people. Jonsson’s comic novel mentions this group (2021: 211).

To conclude, the Sámi are a diverse group with different languages, living in various places. Some are bilingual or even multilingual, speaking the majority language and one or more minority languages. However, knowledge of the Sámi language is often passive or lost due to oppression and political decisions by the Scandinavian states. The process of rediscovering the lost Sámi roots is the main theme in Mats Jonsson’s comic novel.

Changing borders

Both Axelsson and Labba are descendants of families that underwent forced migration. In their works, the trauma that the forced migration caused and the countering healing voice are the main themes. The political background of the forced migration started with the 1751 Lappkodicil Treaty in which the Sámi were recognized as a minority people with the right to use the land and cross borders. The Lappkodicil Treaty was an addendum to the Strömstad Treaty, which defined the border between Norway and Sweden.3 In fact, Norway was a part of the Danish kingdom until 1814. At the Congress of Vienna, the borders between the nations were changed after the Napoleonic Wars. Sweden had lost the war with Russia and had to leave Finland to Russia, but was compensated with the decision that Norway should form a union with Sweden. Denmark was given Swedish Pomerania as compensation.

In 1905, Norway became an independent state, and the union with Sweden was dissolved. New agreements had to be made, also regarding the Sámi and, in particular, the reindeer herding families who moved between the Norwegian summer pastures and the winter pastures in Sweden. These Sámi’s right to decide how to utilize the land in Norway had to be regulated. A new agreement was established in 1919. It implied that access to many areas was denied, meaning that many Sámi could no longer reach their summer pastures. As a result, Sweden selected a large number of families in the Karesuando area to be moved to more southern regions within the reindeer husbandry area of Sweden.

Remembering is important to overcoming trauma. Martínez-Alfaro and Pellicer-Ortín advocate moving beyond Eurocentric perspectives on trauma and memory: “Literary works that give voice to minority groups, silenced memories and their struggles to escape the exclusion and alienation that have traditionally been imposed on them by hegemonic Western forces” (2017: 14). This approach, although the Sámi live in a European and western context, will guide this paper.4

Renaissance: modern Sámi literature in Sweden

Together with writers such as Axelsson and Labba, Jonsson belongs to a group Sámi authors writing in the majority language, which in this case is Swedish. Regarding modern Sámi literature5, Sámi writers can be divided into four types.6

Minority writers have to make decisions before they start writing, as Iban Zaldua wrote in 2009 in his essay Eight Crucial Decisions (A Basque Writer Is Obliged to Face): for example, whether they wanted to write in their minority language or the language of the majority (Broomans 2015). Zaldua’s insights can be applied to the situation of Sámi writers as well. Axelsson stated that she is able to understand and read some Sámi, but apparently, it was not an option for her as she lacks the skills to write a literary work in the Sámi language (Broomans 2022, 131).

The first type contains authors who can write in the majority language as well as in their mother tongue. They want to create awareness among both the majority and their own people. The second type intends to awaken their own people, who urge resistance and, at the same time, present the Sápmi homeland as a safe and isolated biotope. The third type includes authors who want to inform their compatriots, the ‘majority’, about the position of the Sámi people by writing, as Linnea Axelsson does, in the majority language.

Elin Anna Labba could be regarded as a combination of the second and the third type of Sámi writers. In her documentary book, however, Labba does not present the Sápmi homeland exclusively as a safe biotope. Furthermore, she writes for her own community as well as to inform the majority. Labba also uses short Sámi texts in her book.

Jonsson can also be defined as belonging to both the second and the third type. In a way, Axelsson and Labba have their alter egos in characters that in the books belong to the third generation Sámi. This can be applied to Mats Jonsson as well, who is also the protagonist in his own comic novel. However, the three authors represent a new type of Sámi writer. They have the intention of writing about the forgotten history in the Swedish historical canon. A fourth type should, therefore, be added to the division of three types of Sámi writers: the generation that writes about trauma by using history and memory. Axelsson, Labba and Jonsson show the results of political and economic decisions for a minority people. This type lays bare the consequences of ideological, political and economic decisions for a minority people and the fragility of the collective identities of minorities in the face of these interests. In the following section, I will present the results of a previous analysis of the works of Axelsson and Labba. After that, I will focus on healing of trauma by memory and regaining the Sámi identity by analysing Jonsson’s comic novel När vi var samer.

Two stories about forced migration

The epic poem Ædnan (2018) tells the story of Sámi families in the twentieth century and at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The reindeer herding families were driven away from their territories in Norway, and the protagonists tell the story of the loss of land and assimilation, resulting in the loss of culture and language. This changed when the last generation in Ædnan started to regain the Sámi language and culture.

Ædnan. Epos was published in an era in which Sámi culture and history as well as the colonization and oppression they were subject to became more visible in literature and film. As stated above, Axelsson was impressed by the movie Sámi blood (2016), which, like Ædnan, includes references to scientific racism (Josefsson 2018). Besides the effects of forced migration, Ædnan reveals the destruction of the Sámi language, the natural environment, and the landscape of Sápmi, as the Sámi had known it for generations, by the Vattenfall company’s plans to build dams, roads, and hydroelectric power plants throughout Sweden.

In Ædnan, references are made to historical events. One such historical event is the Sameby Girjás process, which plays an important role in the life of the third generation Sámi. The legal action of the Girjás Sami village vs. the Swedish state spanned more than ten years. In 2009, the Sami village sued the state in order to defend its right to the land and in January 2020 the Supreme Court delivered its verdict. Girjás Sami village won the epic land use case. The Supreme Court granted Girjás Sami village the sole right to control who will be allowed to fish and hunt in its reindeer herding area.7

As stated, there are many references to scientific racism in this work, for example, in the part in which Ristin, a protagonist of the first generation, is examined. A doctor investigates and measures her skull and body8:

| With hard tools he measured me |

[Med hårda redskap mätte han mig |

| Learned men in every nook |

skriftlärda män i varje vrå |

| with sharp penhood |

Med sylvasst pennskrap |

| they went through me - |

gick de igenom mig - |

| I understood that a short-statured type took shape on their paper |

Jag förstod att en kortväxt typ tog gestalt på deras papper |

| In royal ink the breed animal was drawn |

Med kungligt bläck tecknades det rasdjuret] |

|

(Axelsson 2018, 147-148) |

The epic poem Ædnan shows the reader the history of forced migration and the effects it had on Sámi families in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The narrators in Ædnan respond to the historical events in different ways, and they all make personal and political choices in the face of colonization and oppression. Axelsson pictures the effects of forced migration in a poetic form whilst Elin Anna Labba investigates forced migration in a journalistic way in her documentary Herrarna satte oss dit. Om tvångsförflyttningarna i Sverige (2020) [The Lord put us here. About forced relocations in Sweden]. Three hundred people were forced to migrate between 1919 and 1932. But these families were not the only ones that underwent forced migration. The Swedish state forced other families to move in order to facilitate housing for the newcomers, a move which resulted in conflicts among Sámi (Labba 2020, 181). Labba’s grandparents were also victims of forced relocation. Herrarna satte oss dit adds to and explains the poetical representation of the forced migration in Ædnan. Labba intertwined testimonies, interviews, documents and letters throughout her work and then added interviews and her own accounts in the parts describing the memories and emotions of the protagonists. Labba is visible as an author throughout the whole book.

She weaves, interweaves and combines stories and fragments of stories, memories and yoiks.9 Sometimes the material consists of just silence and gaps, and here she feels the need to add her own words and sentences, exactly like the nineteenth-century historians used to do, as Hayden White has demonstrated. Labba notices that speaking is a form of healing. The first step in Porsanger’s model for trauma healing is speaking. In An Essay about Indigenous Methodology (2004), Porsanger presents a model developed by Linda Tuhawei Smith, a Maori scholar (Porsanger 2004, 114) and thus following a research agenda containing several relevant notions: for example, healing (at the top) and then, clockwise, decolonization, transformation and mobilization. After mobilization, there follow survival, recovery and development. These terms are visualized in circles having self-determination at the core. Telling and speaking are, therefore, important notions to Labba and other Sámi writers. To tell a story (muitalit) and to remember (muitit) are translated by almost the same words in Sámi, writes Labba, in the language that she loves most (Labba 2020, 12) and that she, unlike Axelsson, can speak and write.10

Labba alternates stories constructed on the base of memories with parts including historical documents and information from interviews and letters. Labba also includes her family in the book and refers to racial biology. She investigates the catalogues of The Swedish State Institute for Racial Biology in order to verify if her family was included: “om de har min familj, och jag hittar dem” (Labba 2020, 142) [if they have my family, and I found them]. She contextualizes Sámi politics by the Swedish state: “Sverige följer här ett mönster som gäller för ett urfolk välden över” (Labba 2020, 181) [Sweden follows a pattern that applies to indigenous people around the world]. Labba compares the situation of the Sámi with the Aboriginals in Australia and the Inuit in Greenland and Canada. The paths the Cherokee and other first nations in the USA were forced to follow are called the Trail of Tears. Labba concludes with a sentence that could serve as a motto for Herrarna satte oss hit as well as for Ædnan: “Urfolks ärvda sår finns nästan aldrig i historieböckerna” (Ibid.) [The transferred wounds of indigenous people are not included in history books].

A story about cultural genocide

In the comic novel När vi var samer, published in 2021, Mats Jonsson (born 1973) writes about the discovery of his Sámi roots and heritage. As an adult, Jonsson discovered that his grandfather kept his Sámi origin a secret. The comic novel, divided into seven chapters, is a mix of autobiographical account and history. Jonsson himself acts as the first-person narrator throughout the story.11 Thus, we can regard his comic novel as a combination of autofiction and history in the form of iconotext, thus a combination of text and images that complement each other. In När vi var samer, Jonsson expresses frustration after discovering being a Forest Sámi. The Forest Sámi were actually not regarded as Sámi people, a point that I will explore more in detail later on. In the comic novel, it becomes clear that his grandfather’s decision to deny the Sámi identity was made under pressure from the Swedish state’s politics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The result was that his children and grandchildren lost half of their history, traditions and language. Jonsson regrets never having listened to the stories about his grandmother’s life whilst the stories about his grandfather’s family were simply never told. At the age of 46, Jonsson stated that the time had come to discover and reconstruct “my history” (2021: 43). Aware of the fact that he had little knowledge, he started to collect information on the Sámi and decided to start with Sámi history. Jonsson presented to the reader events and facts that were not known to the general public. In När vi var samer, many Swedish readers will find new insights into Sámi history. The Sámi were more independent in the past as long as they paid taxes to the Swedish authorities. Furthermore, due to famine in the seventeenth century, a new food supply was imposed: Sámi ‘rennomadism’, reindeer husbandry (2021: 72). Sámi already used reindeer, but reindeer husbandry was not the original way of life for the Sámi as a people.

The colonization and the lack of knowledge went hand in hand with making myths parallel to those of the Native Americans: they could not handle the alcohol brought by the colonists and were always drunk. But the Sámi had already been having knowledge of alcohol for thousands of years through the cultural and genetic exchange with the Swedish farmer, and they only drank on markets once a year (2021: 145).

Jonsson narrates about his research and the way he writes. He also reflects indirectly on autofictional writing from a class perspective. Among others, he refers to writer Alexander Schulman, who had carried out the same type of project. Schulman did research at the University Library in Uppsala and could borrow and read all his ancestors’ archives. That was something Jonsson could not do because in his case there were no archives. Jonsson suggests that this is one of the effects of the class difference. Schulman wrote an autobiographical book about his grandparents and discovered that his grandmother had an affair with the famous literary critic Olof Lagercrantz (1911-2002). Schulman is not the only Swedish writer Jonsson refers to.

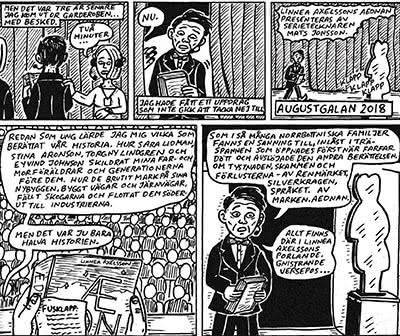

As stated before, in When we were Samer, Jonsson refers to forced migration in the books of Axelsson and Labba (2021: 59). Jonsson is the one who handed over the August prize in 2018 to Linnea Axelsson. In his speech, he mentioned authors not belonging to the Sámi people who described ‘our history’: Sara Lidman, Stina Aronson, Torgny Lindgren and Eyvind Johnson, but according to Jonsson, this is only half of the history. The other half comprises the silence, the shame and the loss of language, but also materials such as silver and land (2021: 187).12

Mats Jonsson, När vi var samer, Stockholm, DALAGO

Published with courtesy of Mats Jonsson.

In his book, Jonsson describes more forced migrations in Sámi history. In 1720, the Swedish king Fredrik I ordered that all Sámi who lived south of what was called ‘Lappmarken’, the land of the Sámi, had to move northwards or end reindeer husbandry and take employment.13 This could be regarded as the start of the border issue. As mentioned above, the 1751 Lappkodicil Treaty assumed a great deal of importance for the Sámi. Jonsson states that the rights of the Sámi had never been so strong as in this period. Not even now in the 2020s (2021: 167). This law dating from 1751 still formally applies. Nevertheless, the Swedish state has over the course of time occupied Sámi land, in conflict with its own law. According to Jonsson, the process of decreasing the rights of the Sámi had taken place unnoticed and was silenced as much as it was illegal (2021: 121-122). When in 2020 it was observed that the forest industry used the land of the Sámi, the industry argued that it was state land. Jonsson demonstrates that this violation of the law already started in the early nineteenth century (2021: 181). The author’s conclusion is that the Swedish company Sveaskog uses the land without any legal support.

Another change of borders already mentioned was the result of the Congress of Vienna treaty in which Norway was added to Sweden, and Finland was lost to Russia. Jonsson concludes: “now Swedishness became important” [Nu blev svenskheten viktig] (2021: 196). Moreover, the theory of racial biology became a tool. According to Jonsson, the development of scientific racism in the nineteenth century played an important role. Anders Retzius, anatomist and anthropologist (1796-1860), introduced the skull index, and race biologists such as Herman Lundborg (1868-1943) started the project of measurements. During the nineteenth century, the oppression of the Sámi became worse and many Sámi rights were abolished. In 1886, the entity Lappskatteland (Sámi land tax country) was regarded as non-existent since the authorities stated that the Sámi did not have the capabilities to take responsibility. As Jonsson remarks, Sweden was on its way towards social democracy, while the rights of the Sámi were declining (2021: 225). The Sámi were regarded as children who needed protection and guidance (2021: 227).

Just as in the books by Axelsson and Labba, Jonsson pays much attention to the story of Herman Lundborg and The Swedish State Institute for Racial Biology in Uppsala. Like Labba did, Jonsson tried to find out if Lundborg also measured some of his ancestors (Jonsson 2021 269-275). In the chapter “Vad hände sedan?” [What happened next?], Jonsson refers again to Linnea Axelsson, who in her epic poem describes the rise of the industry, the hydroelectric power plants and roads built by the Swedish people: “Hur ska våra spår nånsin horas” (2021: 302). [How will our traces ever be heard?] Jonsson also describes how the Sámi in the twentieth century were to some extent given political power (2021, 303). In 1993, they got a Sametinget (Sámi parliament) that would defend and regulate Sámi culture and language. This means that people who belong to the Sámi group can elect their representatives. But Sweden never ratified the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention no. 169,14 probably because she wanted to keep land for its mineral industry. Jonsson criticizes the Swedish state for never having made apologies for the oppression. The Swedish church did make an apology although the 1100 pages ‘white book’, in which the oppression and all the offensive acts by the clergy are listed does not contain anything about returning the land the Swedish church stole from the Sámi (2021:303).

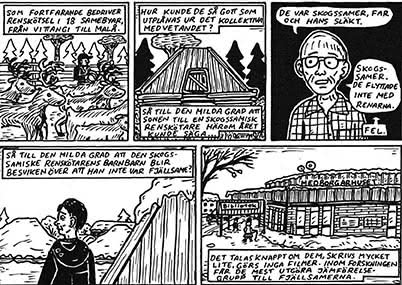

Jonsson about the Forest Sámi

Jonsson positions himself as a Forest Sámi, though he admits that he at first was disappointed that his ancestors did not belong to the Reindeer/Mountain Sámi. He discovers that the Forest Sámi have been erased from the collective memory. They did not move with the reindeer from the winter pastures to the summer pastures, but they raised the reindeer in the forests. Nobody knew about this difference, not even Jonsson. ”Det talas knappt om dem, skrivs mycket lite, görs inga filmer. Inom forskningen får de mest utgöra jämförelsegrupp till fjällsamerna” (2021: 121). [There is hardly any talk about them, very little has been written, and no films were made. In research, they may mostly constitute a comparison group to the Mountain Sami.] The result was that the Forest Sámi became invisible. Jonsson calls this a “cultural genocide,” consequence of Sweden’s policy towards minorities.

Jonsson regards the year 1928 as the completion of colonization. It was then decided that only reindeer herding Sámi were real Sámi, which elicited internal conflicts (2021: 277). Jonsson illustrates this in a story that he calls a “saga,” and it demonstrates the experience that many people had when they discovered, like Jonsson, that they too were Sámi descendants. A young man discovers that he is of Sámi descent and asks for support to find his true self. He gets involved in a group of Sámi but notices that some cannot understand each other. Those who speak Northern Sámi talk in a negative way about the ‘Southern Sámi’, and they use the word ‘New Sámi’ for persons who just found out that they are of Sámi descent. Furthermore, the Sámi who are reindeer herding Sámi speak negatively about what they call ‘City Sámi’, who only can speak Sámi and talk about their complexes (2021: 205).

Jonsson states that the Forest Sámi did not fit in the image of the Sámi because, according to the authorities, they are “en onaturlig hybrid mellan nomader och bofasta” [an unnatural hybrid between nomads and residents]. Their reindeer did not move to other pastures but stayed the whole year in the forests. It was recommended that they did not exist at all: actually, they should have assimilated (2021: 227).

Mats Jonsson, När vi var samer, Stockholm, DALAGO

Published with courtesy of Mats Jonsson.

In regard to the Sámi parliament and the right to vote, Jonsson wonders when a person is a real Sámi. Officially, two requirements must be met: firstly, to regard oneself as a Sámi, and secondly, the person concerned, a parent or their grandparents must have used the Sámi language actively at home (2021: 303). Jonsson concludes that he belongs to the group. At the same time, Jonsson also describes the internal conflicts between the different Sámi groups, so in this way, he acts both as an observer and an outsider.

After his overview of Sámi history, the political decisions and measurements of the Swedish state, their effects on the Sámi people along with his search for his own Sámi identity and the reconstruction of half of his history, he reflects on what he can add to the Sámi culture, especially that of the Forest Sámi. He concludes that he should not ask what Sápmi can do for him but what he can do for the Sámi land. He cannot work as a Reindeer Herding Sámi or engage in handcraft, but he can do something else: “Jag kan berätta” (2021: 326). [I can write stories.] By writing about the lost half of his own history, Jonsson not only writes about the collective Sámi trauma but also overcomes his personal trauma. När vi var samer clearly belongs to the literary works that give voice to minority groups and the silenced memories.

Concluding remarks

Axelsson’s and Labba’s works as well as Jonsson’s När vi var samer share many similarities. The three texts describe the trauma of different generations. The first generation was silenced and feels shame. The second generation experienced a loss of language and identity. Also, in the case of Jonsson, the intergenerational transfer of language and Sámi identity was interrupted because his father never spoke Sámi. The third generation takes up activism and claims Sámi identity. A ‘re-emigration’ to Sámi identity via regaining the language and identity takes place. All works deal with colonization and oppression within the Swedish state’s borders and can be regarded as a trilogy about recovering identity by writing about trauma. The texts also tell stories of continuity and resistance and represent Sámi artists’, filmmakers’ and authors’ personal persistence and artistic will to write about trauma by using memories. The authors use different genres (poetry, documentary and comic novel) while showing the results of political and economic decisions for a minority. Moreover, the presented material shows that the collective identities of minorities are fragile, not only due to political and economic interests, but also for ideological reasons: as a result of scientific racism, the Sámi ended up being regarded as the ‘Other’.

The three texts by Axelsson, Labba and Jonsson fulfil the goal of redefining Sámi identity and adding a forgotten history to an incomplete history written by the majority. The texts are manifestos of politically self-aware authors. In the words of Linnea Axelsson: “Literature is political in and of itself. It bears witness to a perspective on the world, it speaks of the world and its people.” (Vogel 2019).