[T]he State has exercised control of the island [Stjernøya], among other things by […] leasing a substantial area to mining industry within the claimed borders of the appellants [Reinbeitedistrikt (lit. reindeer grazing district) nr.25 and Sara-gruppen (lit. the Sara group), both members of the indigenous, Finno-Ugrian-speaking Sámi people] (§45, HR-2016-2030-A).

With this conclusion denying the right to collective ownership by the appellants over the south part of Stjernøya [Stierdná1], the Norwegian Supreme Court closed a jurisprudential saga started in 2005 in the wake of the adoption of the Act relating to legal relations and management of land and natural resources in Finnmark (Law on Finnmark).2 The case not only highlighted fractures between the dominant Scandinavian group and indigenous Sámi communities but also between two deeply antagonistic spheres of knowledge. At the forefront of economic development of peripheric regions in Northern Norway, mining activities have since the second half of the 19th century indeed gradually entered in conflict with traditional indigenous land-based activities—mainly reindeer herding. Despite the legislative and technical efforts to establish buffer zones to downscale tensions, the narrative opposing modernity and traditional, mining vs. reindeer herding is still a structuring element for identity construction within the Scandinavian and Sámi groups. Or, is it? Haven’t these spheres maybe more in common? After all, both originate in land-based knowledge and cohabit since half a century on the same patch of rugged land exposed to the hostile climate of arctic Norway.

After a brief presentation of the background and of the material used to support this hypothesis, the contribution will highlight the role played by the legal definition of the burden of proof in the scientification of indigenous knowledge. In the third part, the analysis will show the strategies at stake to create a knowledge of otherness to order to build a unified, homogenous Sámi nation. The paper will aim at deconstructing the framework itself of modernity vs. tradition by showing that knowledge formation obeys a specific political agenda by sámi elites. One strategy, essentialization, will be identified as the epicenter of the political and cultural hegemony of reindeer herders.

Mapping land rights on the fault line between mining and reindeer herding knowledge

With incorporation in national law of the 1989 C169 ILO convention’s provisions on the right to land for indigenous people—especially the dispositions of article 14 §1 and §2—the Law on Finnmark opened the way to a systematic reconnaissance by the State of traditionally used land. The process of recognizing land rights, however, is not entirely new, but the systematic approach is. The ad hoc reconnaissance of land rights for the Sámi people can be traced back as early as the 1751 Lappekodisill3—a bilateral agreement between the Kingdom of Denmark/Norway and Sweden, safeguarding, for the first time at the international level the right for reindeer herders to cross-border movements, as well as their corollary right of collective land use. The reasoning behind dates back to ancient Roman law and is based on the jurisprudential principle of acquisitive prescription i.e., connecting factual and legal use of land. The concept was later adapted to the long-term use of land by Sámis as indigenous people. As the Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorites J. Martinez Cobo stated in 1987 in his Study of the Problem of Discrimination against Indigenous Populations, indigenous people are characterized by

a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them. (§379)

Acknowledging the longue durée, the Norwegian jurisprudence gradually developed the concept of immemorial use [alders tids bruk].4 Four years before the adoption of the Law on Finnmark, the Supreme Court clarified in the Selbu and Svartskog cases, the legal framework behind the concept of immemorial use. Immemorial use-based claims must meet four criteria: a continuous, exclusive, intensive, and in good faith use of the land. Law on Finnmark not only capitalized on this jurisprudential definition of immemorial use in §5 al.3 but also systematized in §29 al.1 a reconnaissance process by establishing a dedicated commission in charge of mapping existing land rights in the northernmost county of Norway—the Finnmark commission [Finnmarkskommisjonen/Finnmárkokomišuvdna].

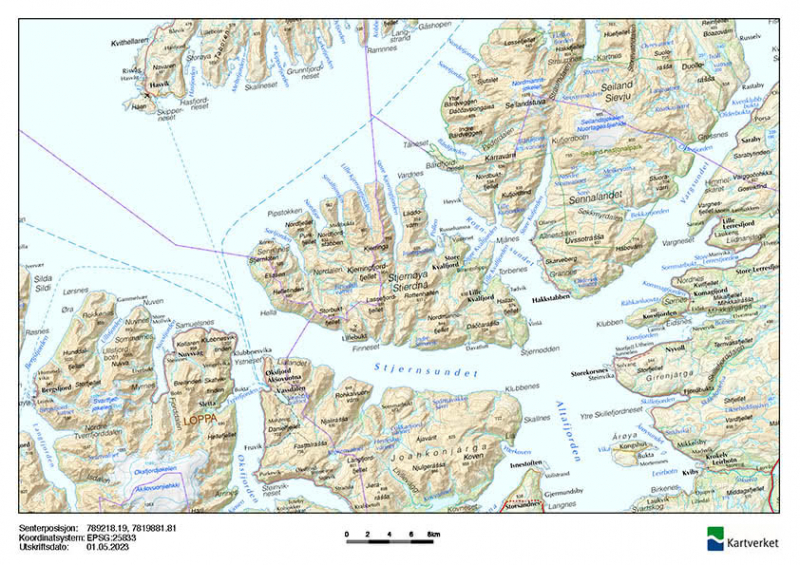

Localization and topology of Stjernøya

© Kartverket / norgeskart.no

Geographically delimited fields were thus progressively considered since 2008—the 10th and latest field, Nordkyn/Sværholthalvøya [Čorgašis/Spierttanjárggas] was opened on October 2nd, 2022. Field 1 encompasses the islands of Stjernøya and Seiland [Sievju], both located 500 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle and 50 kilometers north of Alta [Áltá] in Western Finnmark [Finnmárku]. Eight claims were subsequently submitted to the commission for the field—two of them by reindeer herders, all over the south part of Stjernøya. The first claim, submitted on March 11, 2009, originated from six reindeer herders based in Kautokeino and using collective summer grazing lands on the south shore of Stjernøya. Together, they form the Reindeer grazing district nr.25 and encompass the entire island of Stjernøya. Established by §6 of the 1883 Common Lappish law [Felleslappeloven], reindeer grazing districts play a central role in managing and structuring reindeer herding as a Sámi monopoly. On one hand, this administrative concept mutualizes the risk, especially regarding damage liability, and brings financial stability and transparency. Each member holds shares in the district, so-called siida shares [siidaandeler], and owns part of the herd. On the other hand, just like siida, i.e., the traditional familial organization revolving around reindeer herding, collectivized management is favored for the economies of scale this system provides. Reindeer grazing districts are also key political actors, especially during the annual negotiations with the Norwegian Agriculture Agency [Landbruksdirektoratet] over the industry’s regulation. The second claim (the third to reach the commission) relevant to the study at hand was sent on May 24th, 2009. Although reindeer herders, the applicant is not a member of a reindeer grazing district. It identifies itself as the “Sara-group”, a group of reindeer herders active until 1992 on the south shore of the island since the 17th century (Sara-gruppen 2009: 2, 3). It is composed of six members and centered around a family in its larger conception. Contrary to the Reindeer grazing district nr. 25, most of its members are registered inhabitants of the Alta municipality and use the island for many other activities than just reindeer herding. However, both claims have in common the emphasis put on the traditional, long-term use of the island. The first claim insists on the intergenerational transmission of the island’s usage, e.g., on the necessity for the commission to take into consideration not only the declarations from active members of the grazing district, but also from retired herders (Reinbeitedistrikt 2009: 3). On the other hand, the Sara group puts forward not only the fact that their presence on the island pre-dated mining operations, but also highlights the long history of tensions between them and Christiania Spigerverk [a metalworking company that would later become Sibelco Nordic following its acquisition by Unimin Corporation in 1993]. Nevertheless, the commission concluded in its report published on March 20th, 2012, that these applications failed to prove continuous, exclusive use of the land, despite providing an extensive and heterogenous list of documents (15 documents totaling 27 pages) highlighting their traditional use of land and knowledge as indigenous people. The decision was eventually confirmed by two consecutive verdicts: on August 10th, 2015, by the Finnmark Land Tribunal [Utmarksdomstolen for Finnmark], and on September 28th, 2016, by the Supreme Court of Norway [Norges Høyesterett] in an appeal of the Finnmark Land Tribunal’s verdict.

Over five years, a vast quantity of documents has been produced by the different actors in the case, from applicants to state agencies and juridical institutions. It is impossible to get a comprehensive overview of the material at hand. As of 2023, many of the preparatory documents are still classified and inaccessible to the general public. However, the vast majority of the corpus relevant for the so-called ‘Stjernøya-case’—i.e., the claims and documents ranging from maps to photos, from court decisions to written geographic description sent by the applicants in 2009,5 the 2011 Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research [Norsk Institutt for Kulturminneforskning, abr. NIKU] rapport, the 2012 report of the Finnmark Commission, the verdict of the Finnmark Land Tribunal in 2015, the 2016 Supreme Court verdict as well as, to some extent, the archive of Norsk Nefelin and the Reindeer grazing district nr.25 held at the National Archives of Tromsø—has been published online, almost exclusively under .pdf format on the website of the respective institution. The legal grounds for this transparency lay in the Act relating to the right of access to documents held by public authorities and public undertakings (Freedom of Information Act), more precisely in §3. for the right to public access of “case documents, journals and similar registers of an administrative agency” and in §10 al. 1 and al. 3. for “the duty of administrative agencies [to] keep a journal [and] make documents available to the public on the Internet”.6 Public access changes the nature of the analysis. Contrary to private or classified material, these documents have a potential agency in forming or conveying shared knowledge. Public access thus impacted the methodology employed to analyze the corpus at hand. The discourse analytical approach based on document analysis was framed by the principles of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as defined by Fairclough (2013: 19). Emphasis was therefore put on interdiscursive, and ‘multi-modal’ analysis. The linguistic analysis of texts, and the study of visual documents, maps, and photographs are complemented with a social analysis specific to the research question. Outfitted with this double approach, it is a question of revealing hidden structures of the discourse, identifying interdiscursive shifts to highlight changes in the order of discourse—here the connections between reindeer herding and mining. Another, although complementary, point of entry is the methodology framed by Kristin Asdal and Hilde Reinertsen (2022) in 6 steps. Beyond the interdiscursive and multi-modal approach, documents can be analyzed as place, tool, work, text, thing, and movement. The last point is especially interesting to complement the CDA approach, as it considers the document as essential to the decision process, a mediator (in the sense of Bernard Latour’s Actor-Network Theory) of knowledge.

Along the process, these documents solidified two antagonistic discourses. On one side the discourse of reindeer herders is based on tradition, long-term use of the land, and on the other a modernity-based conception of land exploitation, i.e., mining. Prospecting on the island already started in 1927, with the geological survey conducted by Tom Barth. Eventually, he discovered on Seiland and Stjernøya a large concentration of nepheline syenite, a quartz-free aluminum silicate with application in glass- and ceramic-making processes (Sibelco Nordic 2023). This mineral is part of the plutonic rock type. Nepheline syenite has crystalized during two major phases of magmatic activity within the Norwegian Caledonides during the Finnmarkian Orogeny, i.e., around 500 million years ago for the Seiland/Stjernøya/Sørøy field (Oftedahl 1980: 410). But it was not until 1939 that the mining industry set foot on the island. Stjernøya is, therefore, a crucial chapter in the great history of mining concessions in Norway—a narrative analyzed and contextualized on a national level by Bjørn Ivar Berg (2016) and Svein Lund (2017) and on the local level by Kåre Granli (1986) and Ole Monsen (2011). In 1939, Johan Jørgensen Sara (member of the Sara group) sent a rock sample to the Oslo-based steel and mining giant, Christiania Spigerverk, and six years later a new geological survey of the island was commissioned—more precisely of the Lillebukt [Unna Muotkkadagaš] and Nabbaren [Nápparvárri] fields located on the south shore. A formal leasing agreement was effectively met in March 1961 between Christiania Spigerverk and the Finnmark Land Sales Commission [Jordsalgskommisjon, a state agency, amongst others in charge of managing state-owned land]. Production started in 1963 (Sara-gruppen 2009: 3; Lund 2017). With harsh arctic conditions, operations were not easy to establish. Not only was the life base built at the foot of Store Nabbaren (727 msl.) in an area prone to avalanches,7 but the relentless polar lows forbid extraction during the winter months. Until 2005, operations relied on underground long-wall extraction along a 7 km spiraling tunnel in the south face of Store Nabbaren. In 2001, Norsk Nefelin extended its activities with a new, open pit cut on top of Nabbaren plateau (650 msl.) (Lund: 2017, NIKU: 2012).

Interactions between reindeer herding and mining are inevitable as the flat grounds between Nabbaren and Saravannet were traditionally used in autumn for gathering reindeer before convoying them down to Lillebukt and a transfer to the mainland over the 4 km Stjernøy strait [Joahkku]. A series of legal and technical actions were undertaken to avoid tensions: a stance in open pit activities during the month of September, the installation of barriers as well as the relocation of migration routes in 1985, the acquisition of the Sara group’s properties by Norsk Nefelin in 1963, etc.—all measures to safeguard the “buffersone” [buffer zone] established by the 1963 agreement between reindeer herders and Christiania Spigerverk (Sara-gruppen 2009). However, the 2012 Rapport Felt 1. Stierdná/Stjernøya og Sievju/Seiland. Sakkyndig utredning for Finnmarkskommisjonen (p. V) published by NIKU and commissioned by the Finnmark commission to survey the historical and patrimonial implications of the claimed rights in field 1, summarized the relationship between reindeer herders and mining operators as follows:

Reindeer herding on the island has been heavily impacted by the mining operations of Nefelin. Their establishment not only changed the reindeer herder’s migration routes and feeding grounds for reindeers but has also been the topic of internal disputes.8

The interactions have implications on cultural, political, and economic levels—all of which have been documented.9 One remained unexplored: the epistemological level. More than anything else, these interactions create information, or as Anthony Liew (2007) describes it: “a message that contains relevant meaning, implication, or input for decision and/or action” acquired through activities or situations, historic or present. Information is therefore based on raw material, data that has been processed and organized in such a way that it gives meaning and context. Documents relevant to the Stjernøya case bear the memory of these interactions as they both, capture the generated information as well as store the data. This paper is therefore based on findings from the material gathered i.e., the cross-referencing of geographical points of interest and/or key moments in the history of the island to construct knowledge in adequation with the narrative identity it supports. For example, information about the geological composition of the Nabbaren plateau is present in the documents transmitted by the Reindeer grazing district nr.25 and the Sara group to justify the importance of the location for gathering reindeer. The soil is particularly soft, hence the lower risk of reindeer harming themselves during the gathering period. The special composition of the soil rich in Nepheline is also the reason why Norsk Nefelin started the open pit cut in 2001 on the Nabbaren plateau. The same goes for documents from Norsk Nefelin authorizing and providing logistical help to the Sara group in moving their reindeer from Ytre Simavik [Lássevuonna] to the mainland. Information contained in the documents is anchored in modernity. Everything from the formalism framing the company’s documentation and correspondence to the process of moving reindeer by barge instead of the traditional method of swimming across the Stjernøy strait expressed modernity. And yet, these documents were used to support a claim based on the traditional use of land in court. By doing so, selecting, organizing, and interpreting information in accord with an intended objective, knowledge is first and foremost created—but also shared. These connections linking information to form knowledge are especially relevant for the analysis at hand. A single piece of information, based on one or more raw alphanumeric values (or data), can indeed be used by two opposite spheres of knowledge. Only by combining this particular information with other information will it be loaded with significance.

The ‘scientification’ of indigenous knowledge: a vector connecting antagonist knowledge

In this process, the concept of immemorial use [here you could maybe insert your definition again] plays a key role as information is selected from different sources by applicants to achieve the reconnaissance of their claims. By setting restrictive conditions to the definition of immemorial use, the judge shaped a legal, modern, almost scientific framework where the burden of proof becomes a tool for disciplining non-dominant, in this case, indigenous narratives. To be deemed admissible in a court of law, or at least have a chance to compete with the defendant—in the case at hand the Finnmark Estate [Finnmarkseiendommen/Finnmárkkuopmodat, abr. FeFo, the state-owned agency in charge of managing land in Finnmark and successor of Finnmark Land Sales Commission]—knowledge must include elements of scientificity. The term echoes the concept of ‘scientification’ defined by Weingart (1997: 610) as:

a process whereby the use of and claim to systematic and certified knowledge produced in the spirit of ‘truth-seeking’ science becomes the chief legitimating source for activity in virtually all other functional subsystems.

As such, applications cannot be entirely based on indigenous knowledge or as Bettina Joa, Georg Winkel and Eva Primmer (2018) defined it “local ecology knowledge”—a network of information gathered and shaped by a constant and close relationship with the surrounding environment. This type of knowledge cannot as a whole be formalized as evidence according to chapters 24 to 26 of the 2008 Act relating to mediation and procedure in civil disputes (The Dispute Act).10 Joik for example, the ancestral singing portraying individuals, moments, animals, or locations, but also stories are strangely absent from the applications at hand—although at least one story entitled “Samen som forsvant bak en tåkedott” could be identified in an other source (Larsen 2012: 52). They could fall under the conditions of §26-1 and be considered as “real evidence” if formalized in a written document or under §24-1 and be performed as a form of testimony. But none of the parties choose to do so—flexibility, fluidity, and orality characterize this type of knowledge. Not only does this non-scientific evidence only marginally enter the scope of the Dispute Act but can also easily be challenged by the opposite party. In a legitimacy quest, claims put aside typical local ecology knowledge in favor of information perceived as modern, scientific. This is especially the case for the Sara group which submitted documents emitted by official administrations in conjunction with mining activities. For the Reindeer grazing district nr.25, legitimation takes a different path: international law. By relying explicitly on dispositions outside of the positive Norwegian law, the district connects traditional reindeer herding to juridical internationalism. The procedure, and especially the form made available by the commission constrains the selection of information and therefore knowledge upon which the claims are based on. Only if knowledge is perceived as modern, scientific enough by the parties and the institutions is the claim deemed to have a chance to prosper. In this process of scientification of traditional knowledge, connections are made unidirectionally between reindeer herding and mining information—all with the goal of a reconnaissance of rights upon traditional lands. The process is especially visible through the type of documents attached by the Sara group to their application: letter exchanges with the mining operator, local administrations are provided as evidence of their long-term use of the land (letter from/to Elkrem Nefelin/Norsk Nefelin, 2.4.1992, 2.7.1990, 4.7.1990; letters from/to Reindriftskontoret, 31.8.1992, 3.9.1992, 1.4.1987, 13.3.89; letter from the district veterinary 27.10.1988).

According to the material at hand, the successive holders of mining claims on Stjernøya only rarely used traditional Sámi knowledge to shape or maintain its political dominance. Data, information, or knowledge targeted as indigenous and originating in reindeer herding have been used at an early stage of surveying and managing land and risk in Lillebukt and on Nabbaren. The contract signed in 1963 by the Sara group as well as the consecutive newspaper article published in Ságat on August 22nd, 1963, both highlight the equal right to cohabitation on the island: “[A]vtalen bør legges vel merke til, fordi den anerkjenner reindriftssamenes rettigheter i området, og slik har det nok ikke altid vært før, langt fra det.”11 (Ságat: August 22., 1963 Nr.17/Årg.6) Nowadays, reindeer herding knowledge has disappeared from external communication by the current claim holder, Sibelco Nordic. Despite its objective of “reduc[ing] the impact of our [Sibelco Nordic’s] activities and to bring a positive contribution to the environments in which we [Sibelco Nordic] operate[s]” stated in the 2022 Code of Conduct, the relationship with Sámi communities and especially reindeer herders is absent from the 2021 Activity Report, the 2022 Environmental Social and governance guidelines, but also from the website dedicated to operations on Stjernøya (Sibelco Nordic 2023). Framed by official documents and regulations, the discourse of Sibelco Nordic changed. It is noticeably the case in the application for an extension of the open-pit mining concession on Nabbaren submitted to the Directorate of Mining [Direktoratet for mineralforvalting] on April 2nd, 2014. The lemma “rein” occurs 57 times on 177 pages, with a point 6.11 dedicated to “Reindrift” in the Reguleringsplan med konsekvensutredning for utvidelse av eksisterende dagbrudd for nefelinsyenitt på Stjernøya, Alta kommune [Regulation plan with impact assessment for the extension of the existing open-pit Nepheline syenite mine on Stjernøya, Alta municipality] compiled by Barlindhaug Consult for Sibelco Nordic in 2009. For example, the report incorporates information and data from reindeer herders on migration routes and gathering places:

Nabbaren og området nordover er i utgangspunktet angitt som oppsamlingsområde. Det går en trekklei/drivlei fra Saravatnet til Ytre Simavik, via lia ovenfor Lillebukta.12 (Barlindhaug Consult 2009: 41)

Linking a mining claim to reindeer herding is not only a legal necessity of any regulation plan and impact assessment but also tends to legitimize the long-term dominance of Sibelco Nordic on the south part of the island—by denying an exclusive use of land to reindeer herders.

Connecting knowledge to frame otherness in the national Sámi narrative

Although relevant for managing data–information–knowledge (Liew 2007) interactions at the micro level,13 a definition of knowledge eluding political implications of interactions between political actors is only marginally relevant for the case at hand. Focusing on the formation and “reproduction of political power, power abuses or domination […] including the various forms of resistance or counter-power against such forms of discursive dominance” frames a different structure i.e., political discourse [analysis] (Van Dijk 2004: 1). At the heart of these processes, the formation and dissemination of knowledge play a key role in the perpetuation of dominant cultural and political positions—also within the Sámi group. Critical theory, and especially Foucault, go a step further and believe that knowledge is not a reflection of reality, but intrinsically the product of a power relationship, an understanding of reality actively shaped and constructed. Following Foucault’s concept of a mutually sustained nexus between knowledge and power (1972), the division between modern/mining and traditional/reindeer herding knowledge can be analyzed as politically driven.

These interactions between the dominant Norwegian group through the proxy of mining operations and reindeer herding create a unique discursive space for the perpetuation of a unified, national narrative around the Sámi identity. To define indigeneity, the Sámi need an antagonist construction—an Other to cement their membership to the group. This dynamic is framed by Tajfel and Turner under the concept of ‘social identity’ (Tajfel 1978; Tajfel/Turner 1979) and found many applications in the Sámi narrative. Elsa L. Renberg famously wrote in her pamphlet Inför lif eller död? Sanningsord i de lappska förhållandena [Do we face life or death? Words of truth about the Lappish situation]:

Långt uppe bland fjällen i öfversta Norrland bor sedan mannaminnes tider vår stam. […] Under seklernas lopp har lappen dock alltjämt fått vika för den jordbruksidkande germanska rasen.14 (Renberg 1904: 3)

The same historic dialectical filiation can be found in the applications submitted to the Commission: a narrative based on immemorial use of land (not on the Norwegian concept of immemorial use) against the illegitimate process of colonization. For example, in its application to the commission, the Sara group uses the same strategy and de facto places itself consciously or unconsciously in direct line with Renberg:

Her [Lillebukt] slapp Sara-folket rein på land om våren når de førte rein over Stjernsundet med seilbåt og med god hjelp fra sjøsamene. […] 1963 tok Christiania Spigerverk over Lillebukt og anla gruvedrift der. Det medførte at Sara-folket ikke lengre kunne føre med rein inn i Lillebukt.15 (Sara-gruppen 2009: 4)

Facing otherness is a powerful catalyst for disciplining the construction and perpetuation of knowledge within the group. It brings together different, sometimes opposite poles of the identity, like in the Stjernøya case: Coastal Sámi and actors with concurrent interests within the reindeer herding industry, grazing land districts, and non-institutionalized reindeer herders. Their interests and, at times, opposite knowledge are merged within one global narrative. Through this prism, the end product is equivalent to what Paul Ricœur analyzed under the concept of ‘narrative identity’ (Ricœur 1988: 175):

La synthèse concordante-discordante fait que la contingence de l’événement contribue à la nécessité en quelque sorte rétroactive de l’histoire d’une vie [or in the case at hand, a community], à quoi s’égale l’identité du personnage. Ainsi le hasard est-il transmué en destin.16

The political implications of defining the contours of a homogenous and unified group are the creation and perpetuation of national identity. Although strongly embedded in the dominant colonial discourse on “imagined community” as defined by Benedict Andersen (2020 [1983]), the notion of ‘nation’ has also infused Sámi strategies—once again connecting traditional and modern knowledge. Highlighted by Ketil Zachariassen (2012), the nation-building process among the Sámi started at the turn of the 20th century with the development of a national consciousness beyond the otherwise economically torn apart and geographically scattered Sámi identities. For the first time, knowledge was shared and disciplined into one main narrative. This process culminated in the 1917 Sámi conference of Trondheim, the first institutionalized transnational platform created to share unified and homogenous Sámi knowledge. The Stjernøya case not only plays with the same strategies but participates in the constant (re)definition of shared knowledge within the group. Under the pressure of the dominant narrative, individual knowledge is selected and assembled by the applicants, e.g., in filling out the pre-established form or in providing documents, to create a unified, coherent narrative following the Sámi national discourse. The claims by reindeer herders rely thus on what Foucault defined as the fourth element of knowledge: “[the] possibilities of use and appropriation offered by discourse” (2013 [1972]: 220). To paraphrase Foucault in the context of the case at hand, the information selected for claiming rights on the south of Stjernøya is not the claim of reindeer herders on land rights, but its articulation with other discourse, like nationalism or other non-discursive practices, like the Finnmark commission. At the intersection of this negotiation, singularity plays a central role, like in the photo attached to the document generically entitled vedlagg-kart.pdf and submitted by the Sara group. In a carefully scenarized narrative, the picture taken in 1959 represents Johan Sara wearing traditional Sámi clothes standing on the right side of the picture and facing on the left the representatives of Spigerverk Christiania—CEO Gunnar Schjelderup and lead engineer Olav Øverlie. Tradition vs. Modernity. Mining vs. Reindeer herding. But one picture taken in Lillebukt. The fact that this photo was the only one chosen by the Sara group to legitimize their claim on the south shore of Stjernøya emphasizes the strong essentialization process within the Sámi group. This dynamic is however not inherent to the case at hand, but to all indigenous communities as shown by Linda Tuhiwai Smith (1999: 72). It derives from the colonial framework conferring authenticity to the ‘good savage’ while complexity remained the prerogative of the West. Essentialism has also a second, in-group meaning, based on humanism and the connection with nature. The Stjernøya case can be understood in both ways.

And here resides the answer to why these connections between mining and reindeer herding exist in the first place. The ruling by the Supreme Court is indeed the receptacle of a long tradition of implicit co-construction between dominant colonial actors and dominant elites formed by the colonial state within the Sámi people. A construction straddled across the two branches of essentialism, but with one common objective to preserve hegemony within their sphere of influence. This process is not new and rooted deeply in the history of gradually increasing contacts between Scandinavians and indigenous communities. From 1840 onwards, the political, religious, and legal framework denied any singularity to the Sámi group—culminating in the racial laws of the 1930s. With a movement of resistance emerging between 1900 and 1930, a Sámi elite rose at the forefront. Most of them were active in reindeer herding. Just like Elsa Laula Renberg. Catalyzing individual into shared, nation-like knowledge was the role of purpose-built associations like Norske Reindriftsamers Landsforbund (NRL) which remains until today the main partner for the Ministry of Agriculture in shaping the annual Agreement on reindeer herding [Reindriftsavtale, the agreement governing the economic and environmental objectives of the industry]. Racial politics failed but shaped the narrative of Sámi as nomads, only and entirely nomads—human alter egos of their reindeer. In the process, the political legacy and cultural hegemony of reindeer herders in decision-making structures were strengthened as the assimilation between Sámi and reindeer herders became inevitable. One disposition cemented this approach known as Norwegianization [Fornorskning]: the 1902 Law on Land [Jordlov] and Regulation on land acquisition [Jordsalgsreglementet]. They established the obligation of writing, reading, and speaking Norwegian as their main language to access property—as well as being of Norwegian ethnicity (NOU 2001:34: 426). The negation of their land rights framed the Sámi as nomad reindeer herders, suppressing any complexity of their identity—coastal Sámi for whom agriculture was a part of their way of life were for example absent from this binary narrative. As of 2022, ca. 2,500 individuals were registered as active reindeer herders, representing 562 siida shares [a family group or an individual that is part of siida and is active in reindeer herding]—half of them in Western Finnmark (Landbruksdirektoratet 2022: 5, 118). Put in perspective, they represent 0,04 % of the total Norwegian population and 12 % of the Sámi registered to vote for the Sámi parliament, as of 2021 (Sametinget: 2023). Financially, the industry represents an income of 428 million NOK (Landbruksdirektoratet 2022: 5), equivalent to 0,09 % of Norway’s GBP. And yet, the industry remains a structuring element of the Sámi people, also on a political level. The historically dominant Sámi party—with 17 from the 39 seats in the 2021-2025 Sámi parliament—described the industry in these terms in 2009 on its website: “NSR [Norske Samer Riksforbund] vil styrke reindriftsnæringen som grunnlag for sysselsetting og verdiskaping innenfor en bærekraftig ramme. Samtidig er reindrifta en sterk samisk kulturbærer”17 (NSR: 2009). The mapping of land rights by the commission participates in the same movement of erasing complexity in constructing shared Sámi knowledge. It gave the reindeer herders a platform to vectorize their knowledge of the Sámi as a reindeer herders’ nation. By maintaining this status quo, the classical dialectic mining vs. reindeer herding, the dominant position of ‘authentic’ reindeer herders was strengthened—both in and out of the group as shown by the newspaper coverage of the case. The article published on September 28th, 2016, by NRK summarizing the Court’s decision was entitled: “Høyesterett har talt: Reindrifta får ikke eie Stjernøya”.18 Although based on the fact that the applicants to the Supreme Court were both active in reindeer herding, the use of generic “reindrifta” [reindeer herding] and not “samer” [Sámi] changed, for the public opinion, the perspective on the Finnmark commission’s work. It was not so much about mapping land rights for local Sámi communities anymore as originally shaped by article 14 C169 ILO, but more about the political use of authentic reindeer-based ‘Sáminess’ to gain land rights—and royalties on mining concessions.

Despite sharing the same set of data as elementary material, mining and reindeer herding knowledge form two discursive spaces constructed in opposition to each other. The same alphanumeric values data are combined and contextualized separately according to the political agenda of the group’s elite. However, beyond this dualism inherited from centuries of colonization, data—information—knowledge form, with non-discursive practices, a complex network linking items otherwise perceived as antagonistic. Highlighting, like for the Stjernøya case, the strong interconnection between the two narratives and shifting the focus from the dialectic dominant/minority, opens the way to a more multidisciplinary and multilevel approach. Ultimately, rethinking the opposition between mining (and by extension all ‘modern’ activities including what the Sámi council targeted as “’Green Nordic industry’: […] wind power, hydropower, wave power” in its 2017 declaration) and reindeer herding, give a better understanding of past conflicts in northern Sápmi, e.g. the Alta-saken (1968-1982) and perhaps also some key to resolution on present contentions in Norway: Nussir mine in Repparfjorden (2019 ongoing), Fosen-saken (2010 ongoing). The constant negotiation between opposition and interpenetrations between the two discursive spaces are also featured in popular culture, as exemplified by the 6-part, NRK-produced TV show Vi lover et helvete (2023) (a cliché love story between a Sámi environmentalist and a mining worker with political activism within reindeer herding as backdrop) and the movie Ellos eatnu—La elva leve, a fiction about the Alta-saken (2023) featuring two iconic figures of the Sámi movement bearing the legacy of Elsa Laula Renberg: Sofia Jannok and Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen. On a legal level, this approach can also give a key to better comprehending the reality of claimed land rights. Stjernøya was the first field mapped by the Commission. However, the ongoing case in front of the Utmarksdomstolen in field 4 Karasjok shows that the theoretical and methodological framework designed for this analysis could be key for analyzing the tension arising between Sámi reindeer herders and the local inhabitants on the ownership of Karasjok19.