In Culture and Imperialism, Edward Said underlines the centrality of the construction of imaginative geographies alongside political and military ones and invites us to ponder over mythemes and images associated with land and territories:

Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings. (Said 1994: 7)

Of course, those territories are not just terrestrial but also maritime: seas and oceans, as in-between spaces, are loci of power struggles eminently fertile for ideological constructs as much as fierce armed conflicts and formal treaties. Seas and oceans are not outside or beyond history as Western tradition has sometimes attempted to circumscribe them. On the contrary, as Klein and Mackenthun (2004: 2) note in Sea Changes, their impact on history is “enormous” and real: over centuries, they have served as “agent[s] of colonial oppression,” as “site[s] of loss, dispersal and enforced migration” but also as “agent[s] of indigenous resistance and nature empowerment” or sites of subcultural creation. Seas and oceans are typical “contact zones” as defined by Mary Louise Pratt (1991: 34)—that is, “social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination—like colonialism, slavery or their aftermaths”. A plethora of discordant narratives based on competing ideologies have thus always been sparked by those awe-inspiring and at times terrifying liquid immensities.

In her poetical piece “The Sea Cabinet,” Caitríona O’Reilly confirms the centrality of imaginative geographies next to political and military ones and points to the profusion of stories about oceans and seas, in this case boreal waters. She embarks on a septentrional voyage to explore the Northernness of the Arctic Ocean and complex political and colonial undercurrents at stake around the polar space. As we shall see, her poem combines a strong historiographical component with an ecopoetic one.

Imagination stimulated: museum as “Wunderkammer”

“The Sea Cabinet” is the title poem of O’Reilly’s second collection published in 2006, a collection drenched in the natural world—winds, storms, seas, coasts, lights—and its interactions with the lone self.1 A poetic polyptych cast in free verse over five sections featuring a variety of poetical forms—“The Ship,” “The Mermaid,” “The Esquimaux,” “The Unicorn,” “The Whale”—it pays tribute to the city of Hull’s past as a major whaling port. As she perambulates through the galleries of the local Maritime Museum, the Irish poet is inspired by all the paraphernalia on display: skeletons of various species of cetaceans, whaler’s tools but also ship models, journals, logbooks, paintings, illustrations and hundreds of examples of the folk art and mythemes of the whaler. Her creation is thus a peripatetic text but also a multi-layered ‘cabinet of curiosities’ in the metaphorical sense in which scrimshawed teeth, tokens of love and therapeutic potions mix with harpoons, marine maps, diaries, posters or oddities like a stuffed mermaid. Stories are numerous in this poetical piece: they range from an inventory of the various species of whales, to maritime mythologies and traditional cosmogonies relying on the figure of the great sea mammal, creating in the end a rich maritime anthropology. O’Reilly picks up on and retells anecdotal and grandiose stories about navigation, life at sea, the construction of masculinity in maritime adventure (exciting action, male bonding, individual and collective bravery, the surpassing of oneself, etc.), the attraction for unknown territories, trade and the by-products of the sea. “The Sea Cabinet” also presents many of the distinctive traits to be found in most of O’Reilly’s poetical work. The first trait is her meticulous scholarly documentation and taste for cultural quotation: O’Reilly’s is erudite poetry brimming with literary and historical references, powerful imagery derived from science or the visual arts. Hugh McDiarmid’s “Krang” features, for instance, as a cardinal reference together with Leviathan and Herman Melville in the incipit of the poem as a whole; “The Whale” opens with an allusion to the Arabic alphabet; in “The Mermaid,” the poet summons up images by classicist painter Herbert James Draper or creatures borrowed from Celtic and Norse mythologies. The second trait is her inventiveness with language and syntax: reading O’Reilly’s pieces turns into a jubilant activity as the reader notices how she cleverly controls the positions of words in the line or the sentence, how she plays on verbal texture, uses subtle internal rhyme, assonance and alliterative techniques, and revels in sophisticated and exotic words like “ambergris,” “kilderkin” which is an obsolete English measure of capacity, or “yat-steead,” a term borrowed from Yorkshire folk talk which designates the part covered by the ‘sweep’ of a gate in opening and shutting. Finally, the third trait that stands out in “The Sea Cabinet” is her predilection for multiple standpoints and minute tell-tale details that deepen our insight into the world around us. As Jefferson Holdridge notes:

[O’Reilly] is constantly seeking the angle on the object which will make it hang fire, trying to capture some original focus or discovery of being—a first infatuation with reality, a flame burning in a secret place, an eye and a mode of seeing which is not ours, which we have only partially experienced, but which suddenly deepens our insight. (Holdridge 2006: 18)

Inventories and traditional cosmogonies are to be found chiefly in “The Whale” and “The Unicorn” in which O’Reilly relishes in listing the sundry species of whales—the blue whale, the rorqual, the humpback whale, the sperm whale, the Arctic beluga, the narwhal—and their specificities. She describes the teeth of the Right Whale like “a sieve of vertical Venetian blind” (SC, p. 44, l. 13-14).2 She spicily alludes to the narwhal’s tusk used as a token of love, a walking cane or a food supplement for “crowned or syphilitic heads” alike (SC, p. 43, l. 5-6). She mentions the whiteness of belugas reminiscent of Ishmael’s appalled obsession with the colour white in Moby Dick.3 In the epigraph to “The Unicorn,” she even appropriates an advertisement extolling the almost miraculous merits of a potion made from “true Unicorn’s horn”: from scurvy to King’s Evil or Green Sickness, it seems that no illness is resistant to whale by-products that are literally miraculous. In fact, whatever the species of whale, what prevails is the essentiality of the animal and its status as the symbol or the touchstone of the Earth Ocean, a status that medieval Perso-Arabic cosmogony emblematizes to a degree of unequalled perfection. In fact, in “The Whale” O’Reilly espouses a Persian conception of the universe in which everything that exists rests on the back of a whale: the Earth sits on the shoulders of an angel who stands on a slab of gemstone, which is supported by a giant bull considered as a cosmic beast. The bull itself is carried on the back of the whale Bahamut, suspended in water for its own stability:

[…] God rested the Earth on an angel’s

shoulders, the angel on a rock, the rock on a bull,

and the bull on the back of a whale. Beneath

is water, air and darkness. (SC, p. 44, l. 4-7)

The accuracy of the description allows the reader to trace O’Reilly’s source and confirms the meticulous documentary work that constantly supports her creative writing. Here she most probably cites Zakariya al-Qazwini, a Persian physician, astronomer and geographer of the 13th century and his 1283-1284 treatise Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing.4

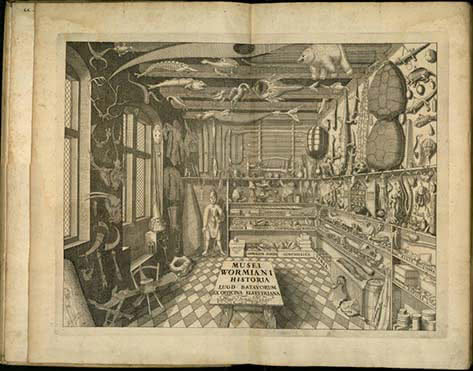

Figure 1: Frontispiece (engraving) from Ole Worm, Museum Wormianum. Seu historia rerum rariorum, Lugduni Batavorum, Ex officina Elseviriorum, Acad. typograph., Leiden, 1655

Bibliothèque numérique patrimoniale de l’Université de Strasbourg, https://cdm21057.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/coll6/id/7748.

At times, O’Reilly’s wandering through the rooms of Hull’s Museum resembles the discovery of a cabinet of curiosities or ‘Wunderkammer’ such as those in which wealthy private collectors of the 17th and 18th century stored and exhibited a wide range of so called “curiosities”—that is, natural objects and artefacts selected not only because they emblematised the variety of God’s creation but because they were rare and extraordinary, eclectic or esoteric.5 In fact, instead of Hull’s Museum, O’Reilly could as well have been walking through Ole Worm’s most famous cabinet of wonders featuring shells, exotic fish, a narwhal horn, a taxidermied polar bear, harpoons and a canoe among other naturalia and exotica.6

Wonders and oddities are indeed to be found in “The Sea Cabinet” next to inventoried museum treasures. In “The Mermaid,” consisting of 22 lines distributed in 7 rhyming tercets (ABA BCB CDC etc.) plus one isolated line at the end which sounds like an irrefutable axiom, O’Reilly goes into cryptozoology, focusing on a fantastic and somewhat scary animal or rather artefact from the deep: a crudely stuffed mermaid which is less reminiscent of Draper’s sirens or the selkies of Celtic and Norse mythology than of the curious beasts and other fairground monsters that made the fortunes of 19th century showmen.7 Medusa-like with her “post-mortem hair,” her “green glass eyes” and her stolid fixity, the phony sea creature traps visitors in “the net of a stare” (SC, p. 40, l. 6-14). It is interesting to note that, as elsewhere in “The Sea Cabinet,” the poet draws our attention to the way exhibits look back at visitors. The latter are watched as much as watching; they are under observation too. Their “voyeurism” is met by the “exhibitionism” and gaze of the objects on display. The reversibility of the gaze, of the seeing and the seen, of which children have a naive intuition, proves as destabilising as the “numb roll of the whale” in icy waters on which the poem closes:

[…] In her fixity […]

Without hearing, or touch, or taste, or smell, or sight

she echoes the numb roll of the whale

in a sea congealed with cold, when it was thought

no beast could be as nerveless as a whale. (SC, p. 40, l. 14-22)

Behind the Scenes of the Whaling Industry

The ambiguity of this false and petrifying mermaid resonates singularly with the ambivalence and grey areas of the whaling industry to which Hull’s Maritime Museum, and O’Reilly’s poem in its wake, pays tribute. As the museum documents, the city’s prosperity has been done and undone by the whaling activity: it began in the 17th century and reached its peak in the first half of the 19th century. By the 1820s, Hull boasted 40% of the UK whaling fleet with 62 ships regularly sailing the Arctic seas, and the city was prosperous thanks to the whale products and industries created to produce them. However, a decline began in the course of the century and the town’s whaling activity virtually ceased in the late 1860s. At the end of “The Whale,” O’Reilly comments upon this decline, emphasizing the permanence of the animal versus the transience of all that is human:

It is they [the whalers] who are in darkness now.

The whale on which their world depended

is elsewhere, free of history, and casts

their antique lives adrift like ambergris. (SC, p. 44, l. 25-28)

In her poems “The Ship” and “The Esquimaux,” the Irish poet refers most specifically to Hull’s last two whalers: on the one hand, the majestic steamer “Diana,” which was trapped in the ice for more than six months in 1866 and then wrecked off the coast of Lincolnshire in 1869; on the other hand, the “Truelove,” the city’s last remaining whaler, which outlasted all the other whalers of its generation.

Of course, it is not the history of the ships themselves that interests O’Reilly, but the history of the men associated with them. Her geography is a human geography based on the images and artefacts seen in Hull’s Museum. O’Reilly thus relates the fate of John Gravill, the captain of the “Diana,” and beyond that of the whaling crews. She also tells of three emblematic figures from the “Truelove,” whose plaster busts are on display in the museum: Memiadluk and Uckaluk, an Inuit couple from the Arctic Baffin Archipelago, west of the Davis Strait, and Captain John Parker, who brought them back to England on board the “Truelove” in 1847 to show his fellow citizens their living conditions.

Heroism and barbarity

The poem “The Ship,” centred on the story of the “Diana,” exalts the heroism and grandeur of the whalers in a contrapuntal manner. Dominated from the outset by the theme of death, it nonetheless underlines the extraordinary courage of these men who experienced absolute adventure in hostile places on the border between the known and the unknown world, who faced extreme perils in their quest for the world’s largest animal, who braved the sea and the ice, the cold and the solitude. The opening lines chronicle the fate of Captain John Gravill, who died on board the “Diana” when it was trapped in the ice of the Far North. O’Reilly insists on “the giant squeeze of ice” which could shatter the hull of the most powerful ships; she depicts the cold, the terrifying noises, the illnesses, the smallness of the men in the face of the white immensity, their gusto and desire to live on the edge of death:

A panel on his grave depicts the ship,

cruelly beset, aslant inside the giant squeeze of ice.

How many nights did her scurvy crew lie,

possessions tied in gaskets by the bed,

hearing the hull shriek like a diptheric child in sleep,

waiting for the shout of the watch? She was not crushed

like her Dundee sister Princess Charlotte,

whose crew returned to blast the splintered hulk,

extract whisky like ambergris from a whale’s belly,

and hold a drunken revel on the ice. (SC, p. 38, l. 16-23)

The whaling community thus appears to be a community of heroes, like John Gravill, whose remains were brought back to Hull, greeted by thousands of penitents and to whom a monument was dedicated, paid for by public subscription.

Yet the concise but striking description of the harpooning of a whale in the second part of the poem undermines the initial image of adventurers and supermen. Like Melville in Moby Dick, O’Reilly does not fail to point out the barbarity of this hunt, the immeasurable suffering of the harpooned animal trying to escape, the violence of the fight, the fiendish devices like the fish-hook beard to make the catch secure:

In the empty museum

in Queen Victoria Square, a whaling-boat protrudes

as though from a half-thawed iceberg overhead,

affording a whale’s-eye view of its sharpened harpoon

of dark soft iron, with stop-withers like a fish-hook’s beard

for lodging deep in blubber, only to be hacked clear.

It is spanned on ready for the chase, and seven hundred

fathom’s worth of line lies coiled like worsted in the boat.

A stuck whale is a fast fish, and dives so quick

a pigging pail must quench the fire the friction starts. (my emphasis—SC, p. 39, l. 28-36)

The change of perspective that causes the reader to momentarily adopt the point of view of the prey rather than that of the sailor, the attention paid to spine-chilling details like the length of the rope needed for the chase or the sparks caused by the friction of this rope on the ship’s rail, the assonance in [r] that prevails in these lines, reflect the savagery, wickedness and peril of the fight between man and animal.

Barbarity goes up a notch when O’Reilly represents the butchering of the sea mammal, all the organs of which (the head, skin, blubber and viscera) fuel a very lucrative trade. This tearing apart of the whale is not depicted directly but suggested by a clever accumulation of terms designating the cutting tools used by the whalers: among these “flensing tools” (l. 36) are tongue and blanks knives, stakes, poles with hooks, spurs for climbing on the back of the colossus, and barrels of all kinds. O’Reilly mimics the intimidating, even threatening power of this league of objects by rhyming them as an “alphabet” in order of battle; but after reviewing them she concludes in the last line on “the whaleman’s glossolalia”. The shift from “alphabet” to “glossolalia,” reinforced by the annotation “spotlit but obscure” applied to the flensing tools, is rich in meaning here: shifting from an ordered set of letters to nonsensical speech as pronounced in a trance or associated with schizophrenic syndromes hints at the hidden flaws of the whaler’s trade: the epic and legendary hunt turns into bloody barbarity. Given over to an almost demented butchery, the animal is debased and desecrated, and with it, the quest of the men who hunt it.

Elsewhere the flensing tools keep an iron repose,

spotlit but obscure, (…).

They hang on the walls, looking as though they might fall

from revenge or neglect, black and contorted as an alphabet:

whale lances, flensing spades, blubber knives

and tongue knives, blubber pricks and seal picks,

trypots and pewter worms, gaffs and staffs and bone gear,

oil funnels, loggerheads, kilderkins and runlets,

spurs for clambering up the slippery sides of whales;

the whaleman’s glossolalia and horizon. (my emphasis—SC, p. 39, l. 37-48)

The ambivalence of the picture depicted by Caitríona O’Reilly is reinforced by the philosophical dimension she resolutely gives to her text. “The Ship” is indeed a vanity poem in the same way as one speaks of a vanitas or vanity painting. The Maritime Museum in Hull erected to the glory of the whaling industry, Arctic sailors and the mythical aquatic mammal appears to O’Reilly as a vast mausoleum; of all these adventures only objects remain, and she cannot but draw a stark lesson about “the tendency of tools to outlast their forgers, their users, / and even the monsters whose bulk they divided” (SC, p. 39, l. 38-39). As if to confirm this, the opening image of the poem is of collapsed graves, eaten away by lichen, while Gravill’s name on his grave marker is corroded by the salt-laden sea air. Altogether, it is a funereal cartography that O’Reilly traces in her poem: she pays tribute to those who distinguished themselves in the whaling adventure but draws our attention to the bloody and fatal dimension inherent in this adventure.

Shady colonial conquest

The second poem, “The Esquimaux,” lifts the veil on another reality, related to the whaling activity of the city of Hull: the colonial phenomenon and its coarse value judgements with consequences for the indigenous populations. Like “The Ship” and “The Unicorn,” this poem is supplemented by an epigraph. It consists of a reproduction of the header of an advertising poster and provides the key to understanding the poem. The young Inuit couple featured here—Memiadluk (l. 17) and Uckaluk (l. 15)—were taken from their homeland to be exhibited in front of British crowds curious to see authentic specimens from the Arctic. The motivation of the captain of the “Truelove,” John Parker, who took them to Hull was certainly a commendable one: to draw attention to the miserable living conditions of the indigenous populations and raise money, but the fact remains that to achieve his goal Parker exhibited them like freaks all over the north of England in the same way that hundreds of Indians, pygmies or Africans were exhibited in other times and places in what some colonial historians call “human zoos”.

The poem consists of 6 unrhymed quintils and is structured in 3 parts. In the first two stanzas (first part) O’Reilly takes the point of view of the young couple and allows the reader to feel her empathy. She projects herself into their plaster heads and makes us appreciate Memiadluk’s pride and composure, which contrast with Uckaluk’s fragility and affliction:

His lower lip’s flatness, the sombre planes

of his skull’s gradual dome

show a resolute teenager’s warrior calm,

but his pretty young wife Uckaluk

grimaces […] salty tears

are squeezed from tight-shut eyes until it is over.

Her upset look suggests it is not over; (my emphasis—SC, p.41, l. 3-10)

Here, the negative echo between “until it is over” and “it is not over” portends yet more suffering to come.

In the next three stanzas (second part), the poet then describes the opposite point of view, that of Victorian visitors, corseted in principles and prejudices about the superiority of the old world, the soundness of Western morals and mores, the duty of civilisation incumbent on the old world towards indigenous populations. The chasm between the Western point of view and the point of view of the young Esquimaux couple is conveyed in various ways: the highly connoted use of the adjective “proper”; the use of oxymorons as in “savagely innocent” (l. 15) or the use of the adjective “flesh-eating” which sounds less like “carnivore” than “cannibal” from British visitors’ point of view (l. 13); the little note about the women in Hull, York or Manchester where the young couple was exhibited wearing whalebone corsets and martingales (l. 12); finally the reference to the masquerade (literally and figuratively) of displaying a crude stereotype of Greenland Man imprisoned in a museum display case with all his traditional paraphernalia:

The good ladies of Hull shudder lightly inside

their baleen martingales and whalebone stays

as Memiadluk, the flesh-eating Esquimaux,

hoists his bow and arrow and strikes a pose

suggestive of savagely innocent ways.

Uckaluk is taught the rudiments of household

economy, the proper care of glassware, china

and knives, and how to braise a leg of beef

(of great practical use in the tundra). (my emphasis—SC, p. 41-42, l. 11-19)

In these two stanzas, we can sense the divergence in attitude between Memiadluk and Uckaluk, a divergence that will ultimately determine their respective destiny. Whereas Memiadluk willingly lends himself to the game of exoticism arousing the prudish ladies’ emotions by performing his role of good savage, his beloved wife undergoes a forced acculturation. Even though they are totally incongruous as emphasized by the unmitigated irony of O’Reilly’s aside—“(of great practical use in the tundra)” (l. 16-19)—Victorian practices are expected to supplant her traditional habits and customs.

Incidentally it is worth observing that, contrary to earlier, there is no reversibility of the gaze between the seer and the seen here. The voyeurism of the genteel population of Northern England is not met by the exhibitionism of the young couple, suggesting a totally asymmetric and inequitable relationship. To emphasize this, the poet points to the young couple’s upset looks and eyes shut: “salty tears squeezed from tight-shut eyes” (l. 4-5); “their eyes closed on a future” (l. 28).

The sad conclusion thus comes as no surprise in the last stanza: it laconically describes the circumstances of the couple’s return to their Arctic homeland and Uckaluk’s death from measles:

And Memiadluk and Uckaluk

keep their eyes closed on a future in which

she dies on board ship of measles only weeks

from home. Memiadluk went back alone. (SC, p. 42, l. 27-30)

“The Esquimaux” is a tragedy in three acts: death awaits at the end of the journey and for the young woman, the plaster cast of her face ultimately amounts to a death mask. Similarly, the name of the ship on which the two young people travelled takes on a different dimension once the story comes to a close: the couple’s sincere love is incisively contrasted with the ambiguous friendship of the captain and the debatable ethos underlying the conquest and exploitation of Arctic territories.8 O’Reilly’s plunge into maritime history thus foregrounds the close association between commerce and colonialism, ethnic prejudice behind the romance of the sea, and subjection and suffering fuelled by the Western ideology of difference.

Conclusion

In “The Sea Cabinet,” a poetic polyptych in constant dialogue with images and artefacts, historiography intersects with literary imagination. Caitríona O’Reilly paints a vivid tableau of Northern waters and their conquest but incisively complexifies it with political and colonial undercurrents. She balances the wonders and dangers of the Arctic, its ambivalence and the ambivalence of its conquerors. She relishes in exploring icy wilderness harbouring extraordinary marine biodiversity; civilization and progress navigating through territories at the edge of, or beyond, culture. But she also draws our attention to adventure and heroism vitiated by covetousness and forgery; she describes conquest fascinated by, but ultimately suppressing, alterity. O’Reilly’s poetical piece reveals the “underside” of traditional maps depicting shipping routes, fishing grounds and the location of Arctic populations’ settlements. She captures the full extent of what the stories, archaeological material, ethnographic objects and artefacts reveal about the deep motivations of the people, their real feelings, their relationships of domination and submission, their greatness and turpitude. O’Reilly’s poem is, in its own way, a map in relief: the poet surveys the museum space, meticulously inventories and positions its elements on the page, and above all gives us the opportunity to hear as well as to see what they conceal. As Peter Carpenter observes: “O’Reilly’s [poetry] thrives on tensions, centrally via the paradoxes of language […], but also those stemming from memories, collective and private, the ‘hiding places’ of poetic power” (Carpenter 2006: 104). The transformative power of polar paraphernalia and vestiges on the Irish poet as a visitor of Hull’s Maritime Museum, as a human being and as an artist, ricochets off her text to inform and transform us in our turn.