In 1814, after centuries of Danish domination (1397-1814), the end of the Napoleonic wars gave to Norway the opportunity to declare its independence. United to the Swedish Crown in a personal union until 1905, the new nation never ceased to show its cultural identity and, on this purpose, began to create its own national narrative (Herb & Kaplan, 2008: 223-226). According to Benedict Anderson, a nation is first and foremost an “imagined community”, based on the feeling of having something in common with other members of this community without knowing them (Anderson, 2002: 19-20). Creating a national narrative was then the first step for Norway to build up its own identity, inspired by history, literature, art, language and folk culture (Herb and Kaplan, 2008: 226).

The European romantic movement and its interest in the Middle Ages guided Norwegians toward the Viking legacy. Established around 1875 by the art historian Lorentz Dietrichson, the Gothic society saw the Viking era (793-950) as the ‘golden age’ of Norwegian history (Halén, 1995: 7-8), the time of valiant ancestors and independence. The rediscovery of medieval literature, especially the Icelandic Sagas, popularized the Viking and his way of life (Lane, 2000: 28-29). To challenge European Historicism’s domination, Norwegian artists and architects agreed to create a national art that could support and spread this new national narrative. Around the 1880s, they succeeded in developing a Viking-inspired style called dragestil or ‘dragon style’ which characterized from now on the artistic and architectural productions in the country (Tschudi-Madsen, 1981: 67).

However, with the turn of the century, a modernized version of this national style was awaited. While the countryside was affected by poverty, the cultural and political elites wished to showcase the economic expansion and the urban modernization implied by the Industrial Revolution (Fallan, 2017: 13-14). The national art had to reflect the socioeconomic progress of modern Norwegian society.

The article, therefore, focuses on this modernization process of Norwegian art at the turn of the 20th century. In this context, how did artists and architects reinvent their Viking heritage to face the challenge of modernity? What was the reception of this new Norwegian style in international exhibitions? To answer these interrogations, this study will analyze a work of art designed by the Norwegian architect Henrik Bull (1864-1953), whose career is one of the most emblematic examples of this period. It shows both the Norwegians’ interest in the ‘dragon style’ and the need to modernize the national artistic production.

Henrik Bull’s name often appears in research about art or architecture, however only two pioneering studies conducted by the architect Thomas Thiis-Evensen (Thiis-Evensen, 1975) and art historian Stephan Tschudi-Madsen (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983) provide an overview of his architectural and artistic production. By emphasizing the stylistic developments and the versatility of his career, they show the main role the architect played in the Norwegian history of art and architecture. This paper aims to complete this field of research by demonstrating Henrik Bull’s contribution to the building process of a national identity at the turn of the 20th century through a stylistic analysis put in a national and international context.

Mainly known for its architecture, Henrik Bull also designed several models for applied arts (goldsmithing, ceramic, furniture, etc.). The end of the hierarchy of arts achieved by Richard Wagner’s concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) gave birth towards the end of the century to a new generation of versatile architects. With the union of arts, these architects contributed to the creation of a national style in various artistic fields (Greenhalgh, 2002a: 19). In 1896, Henrik Bull was commissioned by Den norske Haandværks- og Industriforening (The Norwegian Crafts and Industry Association) of Christiania (Oslo) to design a dining room (fig. 1) for the 1897 Allmänna Konst- och Industriutställningen (General Art and Industrial Exhibition) in Stockholm (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983: 40). For this special event, he created a sofa (OK-18531), a small table (OK-06797), several chairs (OK-06781-92), a main table (OK-06780), three sideboards (OK-06793, OK-06794, OK-06795), and a vanity unit (OK-06796)1. The set of furniture is unified by wood panels (OK-18402) on the lower part of the walls and a carved balustrade. The whole dining room is made of birch or pine wood covered with a mahogany veneer and decorated with similar patterns which gives an overall harmony. The achievement of this total work of art mobilized the best craftsmen of the Norwegian capital: the wood panels and the balustrade were thus made by the cabinetmaker and sculptor John Borgersen, while the furniture was entrusted to the sculptor Lars Kinsarvik and the cabinetmaker G.N. Huseby. Some furniture was also made by leading manufacturers in Christiania (Oslo), such as A. Huseby & Co., C. P. Larsen, Mobeck & Jacobsen, or by De forenede Snedkere (The Union of Carpenters) (Skaug, 1977: 38).

A Style Rooted in Viking Legacy

The ornaments of Henrik Bull’s dining room find their origin in Viking pagan iconography. Furniture and wood panels are decorated with vegetal interlacing, intertwined dragons-snakes and figurative masks. Animal sculptures in the round probably representing lions adorn the pillars of the balustrades (fig. 1). These patterns were rediscovered throughout the 19th century and became characteristic of the ‘dragon style’. Funeral Viking ships and their artifacts were found during archaeological excavations and provided a repertory of ornaments for the artists and architects of that time. For example, the archaeologist Nicolay Nicolaysen published in 1882 a book about the Gokstad ship discovered in 1880. Entitled Langskibet fra Gokstad ved Sandefjord, it contains several plates of drawings showing ornaments from the boat and the artifacts found on the excavation site. Artists and architects were also inspired by the medieval stavkirker (stave churches), built between the 11th and 14th centuries. Their interest is mainly focused on the carved portals, which shows the ornamental syncretism that occurred during the Christianization of Norway from the 10th century on. The pagan patterns of vegetal interlacing and dragon-snake began to decorate medieval churches to express the Christian message. The Vine of Christ and the snake then illustrate the theological struggle of Good against Evil, the victory of Christianity over paganism (Anker, 1969: 447-449).

Fig. 1 : Henrik Bull, Dining room, 1896, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

Photography by Laura Zeitler, 28/08/2022, CC-BY-NC.

The rediscovery of this Viking heritage began with Romantic painters who, like Johan Christian Dahl, traveled in the countryside in search of national inspiration. Facing the gradual disappearance of the vernacular heritage, Dahl was involved in the creation of Foreningen til norske Fortidsminnesmerkers Bevaring (The Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments) in 1844. This society bought several endangered stave churches and promoted inventories of rural buildings. After Dahl’s pioneering work in the 1820s and 1830s (Lane, 2000: 25-28), Norwegian architects took over, like for example Henrik Bull’s father, the architect Georg Andreas Bull, building inspector and then chief architect of Christiania. From 1853 on, Henrik Bull traveled throughout the countryside to draw up an inventory of several wooden farmhouses and churches, especially Urnes and Borgund stave churches in the 1860s (Eldal, 2005: 59). Towards the end of the century, Bull joined the society and, like his father, carried out surveys on medieval churches (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983: 18). These works gave him direct access to national sources of inspiration. Furthermore, drawings were published in several illustrated books, such as De norske stavkirker (1892) and Die Holzbaukunst Norwegens in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (1893) written by the art historian Lorentz Dietrichson (Tschudi-Madsen, 1981: 67), which included Henrik Bull’s surveys. These field studies and publications provided new inspiration but also a better knowledge of the Viking heritage in order to create national art.

By using this type of ornament for the dining room furniture, Henrik Bull was following in the footsteps of a Norwegian production dominated by the ‘dragon style’. This style was born with tourism development in the 1860s thanks to new means of communication by rail and sea (Tschudi Madsen, 1981: 56, 67). It was then mainly used to build railway stations and hotels, especially in the 1880s and 1890s. The achievements made in this period by the Norwegian architect Holm Hansen Munthe, like the Holmenkollen Hotel built in 1889, definitively gave the ‘dragon style’ its status of national style (Tschudi-Madsen, 1981: 69). This neo-Viking aesthetic gradually spread in architecture, but also in goldsmithing with the production of Jacob Tostrup, David Andersen and Henrik Møller. It characterized the furniture designed by the cabinetmaker Lars Kinsarvik as well. (Tschudi-Madsen, 1981: 404-405)

A Style in Search of Modernity: The Fusion with Art Nouveau

Around 1880-1900, the ‘dragon style’ was used in various artistic fields but began to be seriously criticized. At the turn of the 20th century, several voices were raised against the slavish copy of Viking art and argued instead for a new Norwegian art that reflects its own time (Eldal, 2005: 66-67; Kokkin, 2018: 137). Henceforth, this national style should not only represent a sovereign country with its own identity but also show the image of a modern and competitive nation.

Henrik Bull tried for the first time to meet this expectation by designing a modern version of the ‘dragon style’ oriented towards the ideals and aesthetics of Art Nouveau. This new artistic movement was born in the early 1890s in Europe – London, Brussels, Paris and Nancy – in order to break with academic rules and historicist styles. It shared with Henrik Bull the ambition to create a new modern art, which reflects the changes of its time (Greenhalgh, 2002a: 18). The 1896 dining room thus borrows several characteristics from European productions.

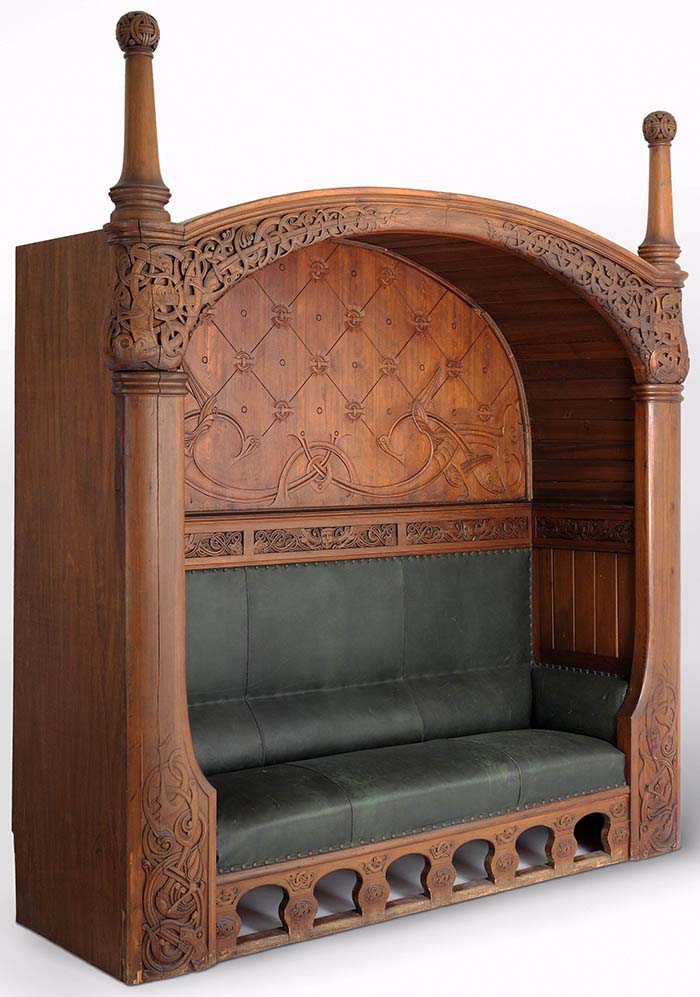

Firstly, the architect designed furniture with simple shapes (fig. 1) that were particularly inspired by the German Jugendstil and the Austrian Sezessionsstil. These styles are characterized by the sobriety and solidity of their furniture production, characteristics shared by the Norwegian vernacular heritage. The function determines the shape of the furniture, but also the placement of its ornaments. The Viking-inspired decoration emphasizes the structure of each piece of furniture, especially on the chairs (fig. 2). Patterns do not cover the whole structure. They are placed in the spandrels of the seat, on the front legs and on the back of the chair. (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983: 40, 42) Secondly, the straight lines of the furniture are softened by using curved lines and arches (fig. 1). The curved shape of the chairs (fig. 2) presents a sober version of the organic furniture developed in various forms by proponents of Art Nouveau. (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983: 30) The theme of nature was indeed a common source of inspiration shared by this new movement and vernacular art. Both promoted a return to the roots. Furthermore, the main sideboard, the sofa, and the balustrade (fig. 1) are decorated with arches of different sizes and shapes. These elements may refer to medieval Romanesque architecture from the stave churches portals. The horseshoe arches on the main sideboard (fig. 1) remind of Japanese architecture, which was another inspiration for the Art Nouveau architects, especially Josef Maria Olbrich. Henrik Bull thus proposed a harmonious fusion of two different artistic movements but sometimes based on common ideas.

Fig. 2 : Henrik Bull, Chair, 1896, OK-06781, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

Photography online by Annar Bjørgli, CC-BY: https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/samlingen/objekt/OK-06781.

Finally, the dining room shows a modern influence of this artistic movement in a freer use of Viking patterns in composition and style (fig. 1 and 2). Most of the ornaments were designed according to the architect’s imagination. Henrik Bull did not copy a precise building or archeological artifact. He also revisited them by using the principle of abstraction (Greenhalgh, 2002b: 57-59). This principle of simplifying decorative ornaments characterized the aesthetics of Art Nouveau and was especially used by architects like Victor Horta, Otto Wagner or Antonio Gaudi. It was also promoted in Norway by the painter and designer Gerhard Munthe and the art historian Andreas Aubert in the process of creating a modern national art (Kokkin, 2018: 18-20). This reinterpretation of Viking art through the simplification of ornament is particularly noticeable in the alcove of the sofa (fig. 3). The architect used the pattern of confronting dragons that traditionally adorns the upper part of stave churches portals but innovated by proposing a personal and stylized interpretation of it.

Fig. 3 : Henrik Bull, Sofa, 1896, OK-18531, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

Photography online by Annar Bjørgli, CC-BY: https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/samlingen/objekt/OK-18531.

Henrik Bull thus borrowed some Art Nouveau characteristics, which spread in Norway at the end of the century. In the 1890s, he traveled to Germany and Austria to complete his studies (Tschudi-Madsen, 1981: 85). He was then one of the first Norwegian architects to get in touch with this new European art. Like most of his colleagues, he probably also subscribed to several new art magazines, such as The Studio (1893), which published the ideas and achievements of the English Arts and Crafts movement, or Pan (1895) and Jugend (1896) related to Berlin and Munich Secessions (Greenhalgh, 2002a: 29). Artists and architects could also seek inspiration in international exhibitions. At the end of the 19th century, the Art Nouveau movement was not very popular in Norway (Kokkin, 2018: 200), but Henrik Bull could rely on the commitment of an ardent supporter of this new art in the country, the art historian Jens Thiis. Curator and later director of the Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum (Mid-Norway Museum of Decorative Art) in Trondheim, he collected for this institution a significant collection of international Art Nouveau styles. Its purpose was to provide new models for Norwegian artists and craftsmen in order to improve their production (Spjøtvold, 2019: 199). In 1895, he went to the opening of Samuel Siegfried Bing’s famous gallery L’Art Nouveau in Paris to buy several objects in this new style (Spjøtvold, 2019: 205). A few years later, at the 1900 World Fair, he bought 92 objects (furniture, ceramics, glass and textiles), mostly French works, for the same museum (Spjøtvold, 2019: 199).

Henrik Bull’s proposal was well received by Den norske Haandværks- og Industriforening of Christiania. Actively involved in the modernizing process of Norwegian crafts through its exhibitions and its own magazine Norsk Tidsskrift for Haandværk og Industri (Fallan, 2017: 24), this association saw in the dining room furniture the way to a future rebirth of Norwegian art:

Man var saa heldig at finde just den rette mand. I en aarrække havde hr. Bull ofret sig for studiet af denne stilart, havde indgaaende tilegnet sig dens karakter og eiendommelighed og besad derfor den nødvendige frihed under stilens anvendelse paa nutidens holmsudstillingen, angav ikke blot, hvad man ønskede at lade udføre, men tillige hvilken stilart, der skulde lægges til grund ved dens løsning. […] Resultatet viser, hvorledes arkitekten med bibehold af stilens eiendommeligheder i forhold og form og en maadeholden anvendelse af dens virkningsfulde ornamentik skabte virkelig ny kunst. […] trods stilens lempning efter tidens krav og kunstnerens hensigt dog familietrækkene let kjendelige frem og fortæller om dets herkomst. Hvad her bragtes var noget efterlængtet, vor blegsotige møbelindustri trængte nyt og friskt blod; det faldt mange ind, at her var veien vist til en gjenfødelse.2

Few years later, the national success of this modern style gave to Henrik Bull the opportunity to design two architectural projects with strong symbolic value, the Historical Museum (1902) and the Old Government Building (1906) in Christiania (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983: 20). While the Norwegian government was about to break the union with the Swedish Crown, the harmonious fusion of ‘dragon style’ and Art Nouveau officially acquired the status of national style, becoming the expression of a fully independent and modern nation.

A Successful Style on the International Scene

As hoped, this new version of the Norwegian style aroused international interest. According to Den norske Haandværks-og Industriforening, the dining room designed by Henrik Bull attracted attention from other Nordic countries at the 1897 Allmänna Konst- och industriutställningen in Stockholm. The idea of modernizing the old national style and its implementation by the architect were well received (Norsk Tidsskrift for Haandværk og Industri, nr. 33, 14 August 1897: 269). The association was indeed awarded a gold medal by the jury of the exhibition (Norsk Tidsskrift for Haandværk og Industri, nr. 36, 4 September 1897: 294). A few years later, it received the same recognition at the 1900 World Fair in Paris.

At the end of the 19th century, the ‘dragon style’ was chosen to represent Norway at international exhibitions and especially at World Fairs. Organized since 1851, these fairs had become major events where great empires could compete by showing their economic and political power. However, World Fairs were also gradually used by several countries or regions under the domination of Prussian, Austro-Hungarian or Russian empires to claim their independence on an international level (Tharaud, 2018: 9-10). At the 1889 World Fair in Paris, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, Norway showed its emancipation from Swedish rule. The absence of Sweden for economic reasons gave Norway the opportunity to exhibit alone for the very first time and then to highlight its own cultural identity. The ‘dragon style’ made its appearance at this World Fair with the Norwegian portal designed by the architect Wilhelm von Hanno and with Lars Kinsarvick‘s furniture. This strategy continued a few years later at the 1893 World Fair in Chicago, celebrating the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus. Norway built a pavilion on the model of stave churches and presented a replica of the Gokstad ship discovered in 1880. A few days earlier, the ship crossed the Atlantic from Bergen to Chicago. The ‘dragon style’ therefore carried a clear political message, reminding that Vikings discovered America first in the 10th-11th centuries (Fallan, 2018: 26). It was then a way for Norway to take its rightful place among the other countries.

Nationalism and Art Nouveau reached their high point at the 1900 World Fair (Tharaud, 2018: 10-11). The modern version of the Norwegian style perfectly reflected this ambiguity of a time divided between a return to tradition and a quest for modernity. It was displayed in the goldsmith’s section in David Andersen’s and Jacob Tostrup’s shops, but the public could also see it on the interior architecture, especially on the entrance portal of the teaching class designed by Henrik Bull (Gerdeil, 1900: 22). Finally, this Norwegian style met with success in the field of furniture with the award of a gold medal for the dining room designed in 1896 (Tschudi-Madsen, 1983: 43). The Norwegian cabinetmaker John Borgersen, who made a part of Henrik Bull’s furniture, was also awarded a gold medal for the furniture he designed himself in this new style (Norsk Tidsskrift for Haandværk og industri, nr. 34, 25 August 1900: 272). Furthermore, this modern version of ‘dragon style’ seemed to please the French art critics who promoted national peculiarities against a cosmopolitan trend of Art Nouveau (Tharaud, 2018: 310-312). Thus, in the French magazine Art et Décoration, Octave Gerdeil praised the Norwegian effort to modernize the national artistic production while maintaining tradition as the main inspiration. He wrote on this subject:

S’il était nécessaire de démontrer que l’art d’un peuple ne se transforme qu’en gardant ses traditions pour base et suivant le génie national, et que les révolutions artistiques d’autres pays ne peuvent lui donner que des indices et non lui montrer une voie dans laquelle il doive s’engager, on trouverait cette preuve à la section norvégienne de l’Exposition. Quoique l’art scandinave nous soit peu familier, on y sent à l’instant qu’on se trouve en présence d’un effort considérable […].3 (Gerdeil, 1900: 20, 23)

The reason for this success lies in the freedom shown by Henrik Bull, who was inspired by European artistic innovations while preserving the authenticity of the old national style. This new Norwegian art was finally well received by the public. The bench and the table presented by John Borgersen were sold in several dozen copies, purchased especially by European museums (Gerdeil, 1900: 25) such as the current Musée d’Orsay (inventory no. OAO 1213).

This new version of the ‘dragon style’ fully met the requirements of that time, marked by modernity and the rise of nationalism. It thus conveyed efficiently the national narrative on the international scene. In the collective European mind, Norway was now related to valiant Viking ancestors who nevertheless belonged to a common legacy shared by the Scandinavian countries. The international success of this style also highlights the economic aspect of this search for a modern national art. This first step in the modernization of Norwegian art gave the opportunity to improve the competitiveness of the Norwegian art industry which, at that time, was behind its European neighbors.

In conclusion, the creation of the dining room in 1896 was an opportunity for Henrik Bull to write a new chapter in Norwegian art history. By modernizing the ‘dragon style’ with new artistic principles, he succeeded in designing a national art that met the expectations of National Romanticism and reflects the modernity of that time.

The Viking heritage remained the main model of this new Norwegian style, but it was reinvented through the prism of Art Nouveau aesthetics. Shapes and ornaments of the furniture share several characteristics with European achievements but keep their national peculiarities. Henrik Bull’s dining room is then one of the first examples of fusion between national art and Art Nouveau in Norway. A better knowledge of the vernacular heritage and open-mindedness towards modern European art appear to be the two main conditions to freely reinterpret the Viking heritage and thus respond to the challenge of modernity. In this way, Henrik Bull put into practice an idea expressed around the middle of the 19th century by several architects in the Intelligenskretsen. To build a new modern nation, this group of cultural and political elites argued for a regeneration of the Norwegian culture through a cosmopolitan graft against the temptation of an isolationist nationalism (Hvattum, 2014: 26-27).

This modern version of the ‘dragon style’ was acclaimed in Norway and awarded on the international scene. Henrik Bull answered efficiently to the political issue by spreading the national narrative of a sovereign and modern nation, while improving the competitiveness of Norwegian artistic production. Back in Norway, the dining room is set up as a model for the country’s artists and craftsmen. After the 1898 exhibition in Bergen, Den norske Haandværks-og Industriforening presented the furniture at its 1901 exhibition (Norsk Tidsskrift for Haandværk og Industri, nr. 48, 30 November 1901: 390) and then gave it to the Kunstindustrimuseet (Museum of Decorative Art) in Christiania (Skaug, 1977: 37). According to this association, artists and architects must now follow the path laid out by Henrik Bull, study the art of the past seriously, and then be able to reinterpret it freely (Norsk Tidsskrift for Haandværk og Industri, nr.34, 21 August 1897: 275). The architect Herman Major Schirmer agreed with this idea and began teaching vernacular architecture through lectures or study trips in the countryside at the end of the century. From 1900 to 1915, this new national style inspired the next generations of Norwegian architects such as Syver Nielsen in Oslo and Johan Osness in Trondheim. It was finally used in the reconstruction of Ålesund between 1904 and 1907. In this period, the architects designed several works of total art that became the most famous examples of the Norwegian Art Nouveau (Zeitler, 2021).