Research on the reception of Old Norse myth since the Middle Ages has been very active in recent years. However, although the French part of this history has been taken into account in some of the latest publications on the reception of the North, it is too often absent from the general discussion. With the exception of the recognition of Paul-Henri Mallet’s work as a turning point in the transnational history of the rewriting of Old Norse myth, French art and letters are mostly absent from overview works. The reasons for this may be manifold, among them not least the decline of the French language proficiency in international research. This is the reason why we have decided to write this article in English. In terms of cultural history, however, the French reception history is an important part of the transnational history of Norse mythology.

While French language proficiency is currently in decline, French was from the seventeenth until the first half of the twentieth century a major language for European educated people—nobles and bourgeois—from Lisbon to Saint Petersburg. It was therefore in French that the Swedish noblewoman Marianne Ehrenström wrote her Notices sur la littérature et les beaux arts en Suède (Notes on literature and fine arts in Sweden) in 1832 and the Danish historian and antiquarian Carl Christian Rafn published his Antiquités Russes d’après les monuments historiques des islandais et des anciens scandinaves (Russian antiquities according to the historical monuments of Icelanders and ancient Scandinavians) in 1850. Hence, a study of the French reception is not possible without taking into account the transnational cultural circulations between the different French-speaking milieus or regions even outside France, Québec and Belgium. On the other hand, France as a country was not as linguistically homogenous as today, but was characterized by important linguistic, cultural and political differences.

In addition to the important role of the French language as a vector of cultural transmission, places like Paris had been major intellectual centers since the Middle Ages and served as hubs for the dissemination of knowledge, especially after the creation of its university. Since then and long into the twentieth century, Scandinavian scholars had been going to Paris or had considered Paris as an important point of intellectual orientation. It was not by chance that the editio princeps of the Gesta danorum by Saxo Grammaticus (1514) was published there, inaugurating its reception all over Europe. Below, we will add more examples.

As mentioned above, the French reception, understood as a multicentric phenomenon has not been yet sufficiently studied. This is all the more surprising as Danish-American scholar Thor Beck presented an pioneering work, Northern Antiquities in French Learning and Literature (1755-1855). A study in Preromantic ideas as early as 1934/35. His two-volume study laid an impressive cornerstone for the systematic study of this part of the history of cultural reception; the intellectual edifice he had projected, however, was unfortunately never finished.1 The present volume wants to incite scholars to revisit the almost abandoned building site, to keep the narrative image, in order to participate in its construction.

Of course, the French reception of the Old Norse myth has rarely been a story of appropriation, as was the case in Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and often in German-speaking countries. The reception oscillated between exoticization, rejection, fascination and adoration, depending on the cultural, social and political contexts. An important turning point seems to have been what Kosselleck called «Sattelzeit» (saddle time), when the French Revolution, the Napoleonic wars, the birth of the modern nation and the invention of the Gauls as ancestors of the French took place. Norse mythology was then often, but not exclusively associated with other peoples, particularly with the supposedly Germanic enemy. This is certainly linked to the mobilization of Germanic myths in the anti-Napoleonic movements in German-speaking countries at the beginning of the nineteenth century. However, the situation is not as bipolar as one could think. As Thomas Mohnike has observed in some recent studies, even the anti-Napoleonic German reception of Old Norse mythology that forms the basis for modern scholarly reception of the Old Norse myth had the milieu of Oriental studies in Paris as an important point of reference.2 It was there that the pioneers of comparative philology such as Friedrich Schlegel, the Grimm brothers and Franz Bopp learned Sanskrit, in the early years with the Calcutta philologist Alexander Hamilton, and consulted and discussed manuscripts that were to elucidate a supposedly Germanic history in close dialog with French intellectuals like Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838) or later Eugène Burnouf (1801-1852).

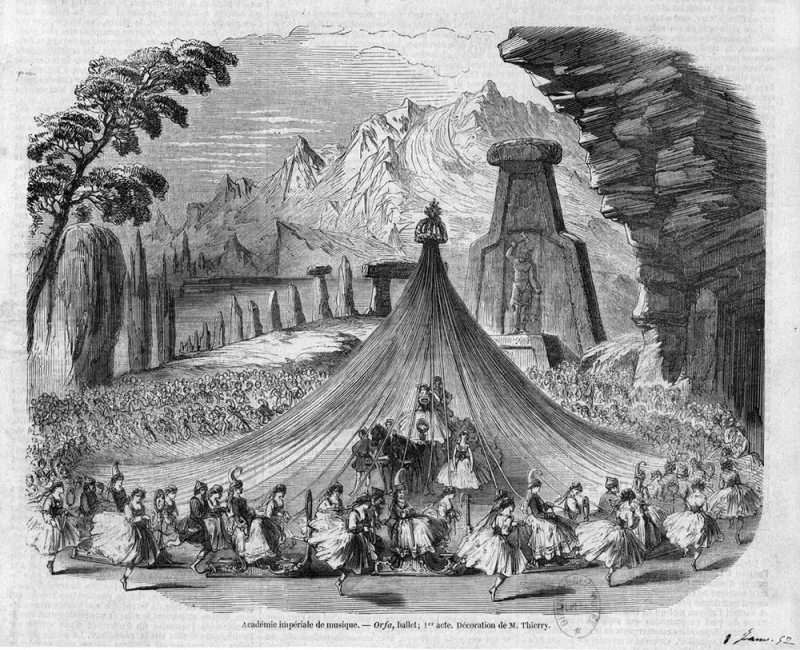

Additionally, the interest in sources and stories of Norse mythology did not diminish because of these political appropriations. Richard Wagner’s operas were certainly an important element for the knowledge of the North even in France, but there were also original French creations such as the 1852 ballet Orfa, written by Henry Trianon, choreographed by Joseph Mazilier to music by Adolphe Adam (a Loki priest drawn by Paul Lomier appears on the cover of this volume) or the opera Sigurd by the Marseilles composer Ernest Reyer (1823-1909), produced in 1884 in Brussels and in 1885 in Paris. The latter is analyzed by Virginie Adams in the present volume. Charles Marie Rene Leconte de Lisle’s (1818-1894) Poèmes barbares (1862), discussed in detail by Francesco Sangriso in his contribution, is another example. In regions like Brittany and Normandy, Old Norse mythology was part of identity discourses. In the politically disputed regions of Alsace-Lorraine, Wothan and Donnar existed in traditions that were interpreted as Rhinelandic.

These examples show that the reception was quite complex, and in certain milieus even dominated by appropriation as part of one’s own heritage: French nobles have long been eager to appropriate the Nordic and Germanic heritage, interpreting French history as a history of conquest by the supposedly Germanic tribes of the Franks over the peasants of the Celtic population. Arthur de Gobineau’s reconstruction of his Viking ancestry is but a late example.3 As Pierre-Brice Stahl shows in his contribution to this issue of Deshima, French-speaking scholars and amateurs produced more than thirty translations and editions of the Poetic Edda during the long nineteenth century. Today, local actors in French Normandy and, to a lesser extent, Brittany, use this common cultural history to found bars and restaurants named after Norse gods such as Odin; there are active Viking metal bands, Viking reenactment groups, and neo-pagan religious congregations on both the right and alternative sides of society. Similar activities take place in Alsace, France-Comté and Burgundy, and to a lesser extent in Paris and many other parts of France, French Switzerland and Belgium.

In the following pages, we want to sketch the history of the French reception of early Norse mythology, as a kind of invitation to further study and reflection.

What is in a Name?

When did French intellectuals and artists start believing that there was a Nordic mythology? To identify important turning points, we used a tool developed by the Google Books team, the Ngram Viewer (https://books.google.com/ngrams/). The NgramViewer makes it possible to study the frequency of a word or sequence of words (Ngram) in relation to all the words in the same corpus in the same year. Google-books has in recent years, as is well known, digitized millions of printed books and periodicals which, by their quantity, are representative of the general production of texts at a given time. For the Ngram Viewer project, they established several corporas. Among these corpora, the French language corpus «French (2019)» is of particular interest to us. It includes both books originally written in French and books translated into French. Of course, depending on the quality of the scan used and the results of the OCR processing, not all the uses of a Ngram are detected; moreover, the quality of the results improves the more modern it is, as the amount of material increases and erroneous or exceptional data have less impact.

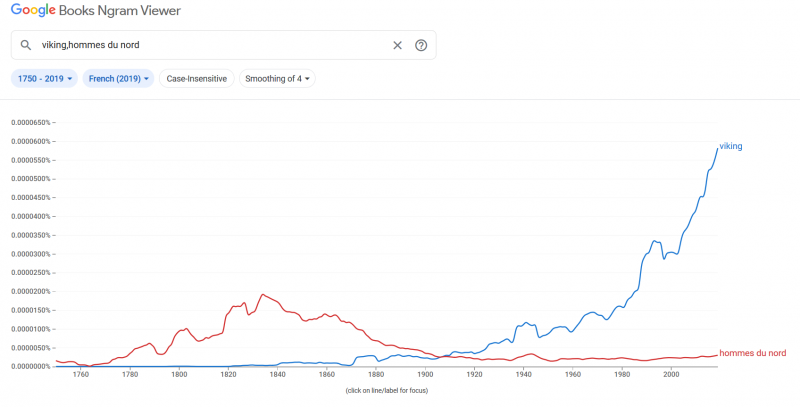

Fig.1: Frequency of the most common French terms for Old Norse mythology since 1500 in the French Google Books Corpus

We launched a query on five frequently used notions to define the corpus of stories: “mythologie scandinave,” “mythologie nordique,” “mythologie germanique,” “mythologie du Nord” and “mythologie Viking” (figure 1).4 First of all, it is very clear that there is no use of either notion before the second half of the eighteenth century. The only visible mention around 1600 is in fact erroneous, it is a text by Mme de Staël catalogued as having been published in 1599 and not, as it should be, in 1799. If people in France knew the stories of the Norse gods and heroes – and this was the case – these stories were not seen as part of a mythology in the modern sense. Mythology became an object of reflection and inquiry after 1750 and thus after Montesquieu’s intellectual bestseller, De l’Esprit des Lois (1748), Paul-Henri Mallet’s Introduction à l’histoire de Dannemarc (1755), James Macpherson’s poems on Ossian (1760 and on) and the time of pre-romantic preparation of cultural and social revolutions of which the French would certainly be the most significant.

Secondly, the preferred term for the set of stories has changed over time. At first, it was mostly described as «mythologie du nord.» The Ngram Viewer allows us to examine the contexts of use. It seems that authors like Mme de Staël and many others, now less well known, used the term in opposition to «Greek» or «classical» mythology. This fits well with the observation made in other studies that Norse antiquity was conceptualized as counter-antiquity. A synonym seems to have been «mythologie scandinave» which is used with the same frequency curve until the end of the nineteenth century as «mythologie du Nord». However, the latter notion almost disappeared after 1900.

After the 1830s, a new term began to compete with the other notions—“mythologie germanique”. This seems to be related to the reception of the research of comparative philologists such as the Grimm brothers and more generally to the advent of comparative philology as the dominant framework of cultural knowledge. The Scandinavian languages and cultures were subsumed in a group with German, Dutch and other languages called from now on “Germanic languages”. “Mythologie germanique” became then the dominating term in French after the foundation of the German Kaiserreich in 1871 and, in parallel, the success of the Operas of Richard Wagner, serving as an important frame of interpretation of Norse mythology until around 2000, although it was followed closely by “mythologie scandinave” that seems to have been often used as a synonym.

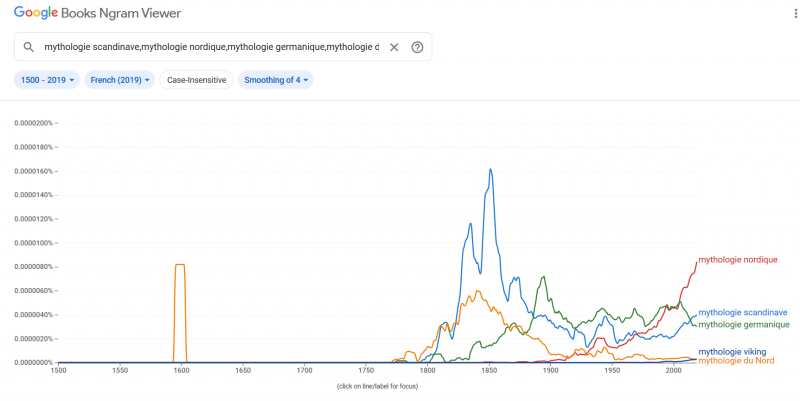

However, the quoted notions have had a strong new challenger in “mythologie nordique” since the 1920s. It became popular after the Second World War, gaining importance around 1950 and replacing “mythologie germanique” by the year 2000 as the most frequently used notion by far. “Mythologie germanique” then lost ground, suggesting that the link to the German language and culture became less important. This is even underlined by the arrival of a new term: “mythologie viking,” which statistically is not yet very significant, but figures on the cover of several introductions to Norse mythology, Neil Gaiman’s Norse mythology (2017), translated as La Mythologie viking being perhaps the most prominent example. The year 2000 appears hence to be another turning point that might be connected to the digital media revolution, the advent of computer games as major providers of fiction. As the Ngram in figure 2 suggests, the Viking entered French letters as early as the 1980s, which was probably related to the success of French and Belgian comic books and graphic novels.

Fig. 2: Frequency of "Viking" and "Homme du Nord" since 1500 in the French Google Books Corpus

One could speculate about the reason for the popularity of the term “mythologie nordique” after the 1950s. It probably had its origin in the dreams of the North popular in European conservative circles, especially in Germany, in relation to concepts such as “nordische Mythologie”. However, it seems that the Scandinavian and German realms became distinct regions in imaginative geographies after World War II, in reaction to the ideological drift of Nazi and fascist circles, and the explicit neutrality of the Scandinavian countries and their model welfare states. This should however be studied in more detail.

This quantitative approach on the frequency of the notions suggests a periodization for the reception of Norse mythology in the French case, which might indeed be useful. It corresponds roughly to paradigm shifts already observed in the reception history of Norse mythology in other European contexts, especially in Scandinavia, Great Britain and Germany as well as to those in the general history of ideas and cultural history in general.

A first period would be the time until 1750, probably to be differentiated into two periods each dominated by one major medium of expression—first manuscripts, and then printing, as we will see in the following pages. Second, during a period between 1750 and around 1840, the idea of a mythology as expression of a people becomes a dominant frame of understanding for this body of stories. However, it will be stabilized and ordered through the paradigm of comparative philology. The period of comparative philology is visible in the Ngram-chart in the use of the notion of “mythologie germanique”. A complementary inquiry for “mythologie allemande” as the direct translation for Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie (1835) appears to confirm this thesis.

The paradigm for framing the interpretation of myth established by the comparative philologies appears to stay valid throughout the twentieth century. However, the time after the Second World War constitutes a rupture, which becomes even more marked in the 1950s, prominent with the growing popularity of the term Viking since the 1980s and the media revolution of the twenty-first century. It will in all likelihood be replaced by a new paradigm. A last point to remember in this context: the French reception is placed into an international circulation of knowledge production. The connected google book search shows that translations have been important media from the beginning, transmitting knowledge to the French reading audience. Additionally, many of the French books refer or use texts in other languages, first mostly Latin, later, in the nineteenth century mostly German, while today translations from the English prevail.

Medieval Beginnings and Humanist inquiries

In the light of what has been discussed above, it becomes evident that we have to distinguish between the reception of elements of the “disorganized body of conflicting traditions” (Faulkes)5 that we call today Norse mythology and the conceptualization of these stories as a body of stories that are called “mythology”. In fact, in the early reception of the stories of the gods of the North, they were not understood as a coherent mythology, but rather as superstitions and belief systems. We have to distinguish between two periods. In the early phase of the establishment of the kingdom of the Franks, the elite converted to Christianism from a religion that certainly shared some content with the religions of Scandinavia. The second period encompasses the period after Christianisation, when the pre-Christian religion of the North was framed as part of the belief or system of superstitions of pagans from the North who had ravaged many parts of the Kingdom of the Franks.

A known testimony for the first case is the widely circulated Historia Langobardorum (History of the Langobards) by Paul the Deacon, dating from the late 8th century and presumably relying on the anonymous Origo gentis Langobardorum and the so-called Chronicle of Fredegar, both probably written at the end of the 8th century. It is worth mentioning here because it was probably influenced by Paul’s stay at Charlemagne’s court and his visits to Normandy, even if it was written later, probably in Montecassino. As is well known, Paul’s story tells of the immigration of the Langobards, a story that not always is peacefully linked to the history of the Franks, from Scandinavia to southern Europe, and refers to Godan/Wotan and his wife Frea/Freja as two of their gods. The contest between Godan and Frea is narrated as a sort of foundation myth for the Langobards that explains the name of the people (“longbeards”), even if Paul has some reservations. The text was later known in most centers of learning thanks to many copies.6

The second period can be traced through several medieval texts such as annals, chronicles and vitae.7 While some of these texts report earlier events, most of them are contemporary of the Viking period. However, reception of Norse mythology is framed by the more general discourse on the medieval North. Among these texts, we can mention the annals, linked, for example to religious centers: Annales Bertiniani [Annals of Saint-Bertin] (8th-9th century), Annales Vedastini [Annals of Saint-Vaast] (9th century), Annales Fontanellenses priores [First annals of Fontenelle] (9th century); or to the royal power: Annales regni Francorum [Royal Frankish Annals] (8th-9th century). We also have chronicles or histories such as the Chronicon (9th century) by Adémar de Chabannes ; De translationibus et miraculis sancti Filiberti [Translations and Miracles of saint Philibert] by Ermantare of Noirmoutier ; Historia Remensis Ecclesiae [History of the Church of Reims] (10th century) by Flodoard of Reims; Historiae [Histoiries] (10th century) by Richer of Reims; Historiae [Histories] (11th century) by Raoul Glaber; De moribus et actis primorum Normanniae ducum [Concerning the Customs and Deeds of the First Dukes of the Normans] (11th century) by Dudo of Saint Quentin; Roman de Rou (12th century) by Wace. Finally, there are vitae and gestae: Vita Karoli Magni [Life of Charles the Great] (9th century) by Eginhard; Gesta Normannorum ducum [Deeds of the Norman Dukes] (11th century) by William of Jumièges; Gesta Hludowici Imperatoris[The Deeds of Emperor Louis] (9th century) by Thegan of Trier; and miracles, such as: Miracula sancti Benedicti [The miracles of Saint Benedict] (9th century) by Andrew of Fleury.

In these writings, the Scandinavians are mainly perceived as invaders. These texts were often written in centers of Christian learning, which had been victims of Viking expeditions. It is therefore above all a pejorative vision that is transmitted. Some of the descriptions and motifs used by the medieval authors will have a long posterity.8 While the reception of the Old Norse religion consists mainly in an opposition to Christianity through the qualifier of pagan or through the assimilation to Satan, mentions of Nordic deities, although rare, do exist. There are several mentions of human sacrifices to the god Thur/Tyr/Marth in authors such as Dudo de Saint-Quentin, Guillaume de Jumièges, Benoît de Sainte-Maure, Wace, or in texts such as the Grande Chronique de Normandie. On the other hand, there is no description of the Old Norse belief system. Thus, apart from the mention of sacrifices, which serves mainly as a reason for condemning and devaluing these «men of the North», there is no description of rituals or ceremonies.

The medieval sources thus suggest some, though largely superficial, knowledge of what was perceived as pagan beliefs. The situation changed profoundly with the advent of the printing industry in combination with humanist philology and thereby the augmented circulation of knowledge from the North in Europe in general and in the French-influenced part in particular. As elsewhere, a major source of knowledge for the Nordic stories about Odin, Thor and Frigg in the beginning of the sixteenth century was a work that expressively did not present them as mythology or religion, but history: Saxo Grammaticus’s Gesta danorum. As has often been noted, this ambitious medieval history of the kings of Denmark, written around 1200 in Lund, was to begin with—perhaps because of its length and therefore copy costs—not the international success it could have been. The book had to wait for the spread of the printing technology in Europe and for a young and ambitious Danish scholar, Christiern Pedersen, to become a close collaborator of the famous Parisian printing office of Jodocus Badius, to make its breakthrough.

The choice of Paris was not incidental. Paris was by then one of the flourishing centers of the new medium of the time, the printing press, and connected new industries such as publishing houses and book traders. Additionally, it was one of the centers of humanism, the closely connected European intellectual movement that worked for reliable editions and interpretations of classical texts. Saxo Grammaticus’s style, “inspired by classical Roman literature,” as Friis-Jensen remarks,9 became fashionable and interesting again around 1500, as was his exhaustive presentation of the histories of kings and heroes of the North, proving by style and content that Northern Europe was not only a place of barbarians and pirates. The edition was widely circulated with several reeditions in Basel and Frankfurt all along the century and beyond, and the text formed a major source of knowledge of the North for European intellectuals in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The Gesta danorum was the first printed book in which the gods of the North appeared, although only partly as gods: Saxo had interpreted them mostly in an euhemeristic manner as kings, princes and warriors that were deified in retrospect. This led to reception situations in French literature in which certain myths would be retold as history and not as part of a non-classical mythology or religion, as we will see.

However, perhaps more important for the reception of Norse mythology in French intellectual circles were two other North European readaptations. Firstly, the much too little studied histories of the Nordic countries written by the Hamburg historian Albert Krantz (1448-1517), particularly his Chronica regnorum aquilonarium: Daniae, Suetiae, Norvagiae, published in 1546 in Strasbourg with reeditions in 1575 and a German translation in 1545. Secondly, Olaus Magnus’s Historia de gentibus Septentrionalibus, published in 1555 in Rome, translated into French and published in Paris in a slightly abbreviated form (ca. 550 pages) in 1561 under the title Histoire des pays septentrionaux: en laquelle sont brièvement déduites toutes les choses rares ou étranges qui se trouvent entre les nations septentrionales. Both Albert Krantz and Olaus Magnus highly rely on Saxo’s text,—Olaus Magnus also relies on Krantz – but adapt their structure and presentation of the knowledge of the North to the expectations of a sixteenth-century audience. Whereas Saxo’s and Krantz’s books are mostly royal family histories, Olaus Magnus’s work is more of a cultural history, comprising description of animals and plants, climate, historical monuments like rune stones, habits such as sorcery and skiing and probably the first printed introduction to the runes. It is through this book that Europeans learned about Adam of Bremen’s descriptions of the temple of Uppsala and the adoration practices of the Norse gods. Although the French edition has copies of many of the influential engravings of the original edition, the illustration of the Uppsala trinity Thor, Othinus and Fricco is not included.

Another vector for the transmission of knowledge of the North in French learning was the work of François de Belleforest (1530-1583), a versatile writer and translator, known for his translation of Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia, his Histoire universelle du monde (1570) and particularly his translation and continuation of Mathieu Bandello’s novellas in 7 volumes under the title Histoires tragiques (1566-1583). The latter functioned probably as an important intermediary, if not direct source of inspiration for some of Shakespeare’s dramas with Italian topics and notably for his Hamlet, a story originally found in Saxo, but adapted to the taste of the time by François de Belleforest in the 5th volume (1573). The fifth volume is the first of the series with his own inventions and contains besides Hamlet—called Amleth by Belleforest as in Saxo—a second novella adapted from Saxo, the story of Saint Canute. Both stories reflect on the stereotype of the barbarous habits of the people of the North by insisting, however, on the fact that they could serve as an example even to a Christian reader of the sixteenth century. Albeit the fact that Amelth could not yet rely on God’s help as he had not yet “cognoissance d’un seul Dieu” [knowledge of a single God]10, he knew what was good and virtuous. As people like him were not yet baptized, it should not be our aim to imitate them, but “à les surmonter, tout ainsi que notre Religion surpasse leur superstition, et notre siecle est plus purge, subtil et gaillard que la saison qui les conduisoit.” [to overcome them, just as our Religion surpasses their superstition, and our century is more pure, subtle and cheerful than the period that led them.]11 It seems important to us that the heroes here are treated as examples for the noble reader to learn appropriate manners. Amelth (and the tyrant Balderus, mentioned en passant) are presented as counter-models, or as models that need to be outdone.12 The people of the North are in this perspective not different from the implied audience.

The position is slightly more ambivalent in his Histoire universelle du monde (1570), where he discusses the status of the Goths that, “selon les escrits des anciens ont esté, & sont encore des plus beaux hommes de la terre tous bien proportionnez, & de stature digne & d’estre admirée & louée” [according to the writings of the ancients were, and still are, the most beautiful men on earth, all well-proportioned, and of stature worthy of admiration and praise]13. They are thus certainly of noble nature, and it is not astonishing that they conquered Rome. De Belleforest discusses their claimed Germanic origin, which he doubts. When describing their religion, he quotes the Uppsala-trinity with Thor as the main God, “lequel ils paignoyent couronné & ayant vn sceptre en main, & douze estoiles autour de sa teste” [which they painted crowned and holding a scepter in his hand, and twelve stars around his head].14 He discusses its power to make the weather and its relation to Jupiter and Janus, before swiftly naming Othim [sic!] and Frigge as equivalent to Mars and Venus, quoting as his sources Johannes and Olaus Magnus as well as Saxo. He continues by mentioning Mithothin, Rostar and Froé, which he considers as minor gods.15

To consider the people of the North as Goths will remain an important point of reference for French writers before the advent of comparative philology. However, there were rival propositions, such as those coming from Normandy. In his Histoire générale de Normandie (1631), Gabriel du Moulin (ca 1575-1660) describes Norway as the ancient Normandy, giving as his source Krantz. He describes the old Normans as barbarians: clothed in fur, subsisting only on dairy products, meat and fish, clinging to their pagan beliefs with “Thur, Wodan & Fricco” as their central gods. He thus refers to the same Uppsala trinity as de Belleforest; however, as the spelling reveals, not to the same source, but probably Krantz. He knows more about Odin/Wodan and interprets Fricco as male, although he remains a god of lust and peace. The cruelty of the Normans is explained by their ignorance of the true God, and of course, they will convert to Christianism “auec pureté & ferueur” [with purity & passion]16 as soon as it is possible.

Knowledge of the pre-Christian religion of the North seems to have remained on this level of information until the mid-eighteenth century. At times, it was complemented by elements from scholars of Tacitus like Beatus Rhenanus, some other classical sources or, rarely, through the reading of occasional Nordic books coming to Paris and France such as Olof Rudbeck’s Atlantica (1672), Johannes Schefferus’s Lapponia (1673) or Thormodus Torfæus’s Historia Rerum Norvegicarum (1711). The gods of Norse mythology appeared in works of universal history, the history of England and Germany and seem to have been part of the common knowledge of cultivated men.17 They were linked to the Goths, the Germanic or the Norman people, between whom the relation was not stable but reconfigured depending on the needs or ignorance of the author. However, it appears that this was more a question of access to sources than of indifference; the history of the North then became more and more a history of Gothic heroes, perhaps in reaction to the importance of Sweden in the political 17th century. A wonderful example is Georges de Scudéry’s (1601-1667) epic poem Alaric, ou Rome vaincue (1654), dedicated to queen Christina of Sweden, in which the king of the Goths is called by God to punish Rome. However, even if Alaric is the tool of the true God, de Scudery does not hesitate to depict in detail the sacrifices to the Norse gods that he had learned about through Olaus Magnus or others, calling them the feast of Thor, “Thore que nous tenons pour le plus grand des dieux, Et qui vit comme Frigge, avec Othon aux cieux.” [Thore whom we hold to be the greatest of gods, And who lives as Frigge, with Othon in heaven.]18

The Liberty Legend and Oriental Fascination (1750-1830)

The eighteenth century in France is often described as le siècle des lumières [the century of the Enlightenment] that led to the revolution of 1789 with its well-known impact on the political system of the nineteenth century and beyond. It is often rightly characterized as a period of rationalization of thought, science and industry, a time in which a critical approach to religion was propagated and the concept of liberty gained importance. However, it was also a time when the consequences of the expulsion of the French Protestants, the Huguenots, were to be felt, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, and the two aspects were certainly linked. These French-speaking Protestants, mostly Calvinists, fled in large numbers to other Protestant countries or to places where religious freedom was granted. In their new countries, this resulted often in a huge intellectual and economic boom, the Geneva area, London, and Berlin becoming for example intellectual centers of French thought and literature in their own right. The impact could also be seen in Denmark and Sweden.19 In France, the result was ambivalent – Protestants left important parts of the societal building to the advantage of some and disadvantage of others.

Many influential French writers and thinkers came from these Protestant backgrounds or were influenced by them; questions of freedom and religion, domination and expulsion, community and belief were central to their concerns. Some of them played a central role in the history of the reception of Norse mythology, notably the Genevan Calvinist Paul-Henri Mallet, who came from a wealthy Protestant family.20 In his influential works on Norse history and Old Norse mythology, the concepts of freedom and liberty were made operational for the understanding of stories of Norse gods and heroes. He was in turn inspired by Simon Pelloutier, the son of a French Waldensian family from Leipzig and Berlin and author of Histoire des Celtes, et particulièrement des Gaulois et des Germains (History of the Celts, especially the Gauls and Germans, 1740) and Montesquieu’s De l’esprit des lois (The Spirit of the Laws, 1748). Montesquieu, in turn, had married a wealthy Protestant woman at a time when Protestant worship was banned in the Kingdom of France.

It is not the place here to discuss in intenso the importance of Paul-Henri Mallet’s Introduction à l’histoire du Danemark (Introduction to the history of Denmark, 1755) and its accompanying source book Monuments de la mythologie et de la poesie des Celtes, et particulierement des anciens Scandinaves (Monuments of the mythology and poetry of the Celts, and in particular of the ancient Scandinavians, 1756). It presented for the first time a comprehensive, from a Copenhagen point of view, state of the art introduction to the early history of the kingdom of Denmark, the Pre-Christian religion of the North and the main aspects of its mythology as mythology in a French and thus internationally fashionable language. As Julia Zernack noted, there was little new in the book from a Scandinavian point of view. For his Edda-translations, he was relying heavily on Resen’s Edda islandorum (1665), which in turn used Magnus Olafsson’s restructured Laufas-Edda and Latin translation. For his presentation of religion and history, Mallet was inspired by Bartholin, Dahlin and many other Danish and Swedish works of the seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century.21

What was new, though, was that it translated this local knowledge into the forms of discourse compatible with the French Enlightenment intellectuals, especially Montesquieu, and astonishingly,22 especially in its second edition, with early romantic thought, inspired by Ossian and the adoration of the natural and sublime.23 This combination could be an effect of the ambiguous situation of the authors, who are part of the French-speaking intellectual sphere but outside the Parisian and Catholic center.

Thor J. Beck structured his above mentioned two-volume study on Mallet and his French successors around two main aspects or mytheme complexes that summarize the intellectual potential for the French intellectuals in this sense.24 The first volume is devoted to “the ‘Vagina Gentium’ and the Liberty legend,” subjects well known for Scandinavian scholars from the Nordic Gothicist movement. However, Mallet and his successors saw the history, poetry and religion of the North as expression a polytheist religion shared by all Europeans, summarized under the term “Celtic,” which was destroyed by the Roman Empire and later by the Roman Christian religion. The opponents to the Roman Empire came from the Germanic forests and the Gothic North that defended liberty and defeated the Roman Empire. The reference to the French ancient régime and its supposed link with the Roman heritage was probably obvious for the reading public. Scandinavia became hence a place of origin for potential revolutions. The revolutions were caused by youthful people from the North—either presented as Germanic, Scandinavian or most often Celtic and thus potentially even French in the rewritings of many of Mallet’s readers such as Thomas, Bailly, Bonstetten, Chateaubriand, Mme de Staël, Pierre Victor, Capefigue, Ozanam, Malte-Brun and many more.25

Beck’s second volume is devoted to the “Odin Legend and Oriental Fascination,” taking its point of departure in the legend of Odin as an Asian chieftain having immigrated to the North and founded several kingdoms on the way. The story was already found in the Prose Edda and the Heimskringla, where it served as a means to integrate the history of the North into European and universal history by making Odin either an ancient prince of Troy or at least a powerful king coming from a rich and prosperous region as a reaction to Roman imperial politics. This alternative migrant history of a potentially classical hero in line with the Greek-Roman migration of Aenas to Latium was of interest to many French intellectuals. It resonated with the discovery of the Indo-European language group at the end of the eighteenth century and its possible Asian origin, and it laid as well the ground for sometimes enthusiastic appropriations of Norse myth and culture. These appropriations would only become problematic in the second half of the nineteenth century when rising nationalism and nationalistic comparative philology decomposed the blend of people, myths, languages, and cultures that made up Europe before the Saddle-Period (‘Sattelzeit’). Fascinatingly enough, Mallet’s reader did not have to choose between Oriental Fascination and the Nordic cradle narrative; they were in fact compatible, as Beck had already underlined, for Mallet and many of his French readers:

Whenever [Mallet] deals with this [Paneuropean] “Celtic” religion, he is (because of his Celtic illusion) really for the most part speaking of Scandinavian mythology, but also of Oriental influence since Asia is supposed to be the cradle of his Paneuropean Celtic nation, an idea shared by his readers for several decades.26

In fact, many of Mallet’s readers were inspired by his narratives as repertories of mythemes of Norse culture, reusing them not always in the sense Mallet had intended. As Julia Zernack observed rightly, “such a vivid and detailed picture of the religion of the North was not available anywhere else at a time when ‘primordial’ cultures and religions were beginning to be discovered in the eighteenth century.”27 Beck adds:

We shall see that he prepares the way for a Court de Gebelin, a Charles Dupuis, and thereby Creuzer’s doctrinaire, if romantically inspiring, symbolizations of Greco-Roman myths. Mallet broached problems in comparative religions, which were to become the subject of romantic orientalism for well-nigh a century after his books had appeared in the first edition.28

Beck’s second volume gives many examples of re-appropriations of Mallet’s two mytheme complexes until about 1830, and students of the reception of Norse mythology in French literature should return to this exhaustive treasure, even if of course many of his contextualizations and evaluations have to be reconsidered, as it was published in the beginning of the 1930s. Along the mentioned authors in the quotation above, he analyzes many forgotten or no longer read texts like Charles Pougen’s Essai sur les Antiquités du Nord (1797), Count de Tressan’s works such as Histoire d’Odin, Conquérant, Législateur, enfin, Dieu des anciens Scandinaves (1777), Bailly’s Lettres sur l’Atlantide de Platon et sur l’ancienne Histoire de l’Asie (1779) or by many other intellectuals interested not only in the North but above all in Asia. Madame de Stäel, Bonstetten and the geographer Malte-Brun certainly played a similar role a generation later in the beginning of the nineteenth century.

What seems important is that many authors in fact identified with the people of the North, as they saw in Odin and the other gods part of an original European religion that united Europe before they adopted ideas and practices from the South. In this sense, the Belgian writer Charles Marcellis published as late as 1829 in Paris the epic poem Les Germains with Odin as its main protagonist leading the people of the North against Rome, the symbol of the “peuples civilisés, mais corrompus, des institutions sages mais usées par le despotisme” [civilized but corrupt peoples, wise institutions but worn out by despotism]29.

The Long Nineteenth Century

As other European regions, the French nineteenth century was marked by the nationalization of societies, political thought, and imaginative geographies and by the professionalization of literary and cultural studies. French changed from the language of elites into a national language, which caused problems not only in Belgium and in Switzerland. More clearly than before, two different cultural fields that carried knowledge of the North were differentiated—art and science, although there was of course an interaction between the two, in France perhaps more intensely than in other countries. Universities and learned societies became the place of production of scholarly knowledge. Novels, magazines, theatres and concert halls developed into a bourgeois public cultural sphere, where conversational knowledge about the North was elaborated and the North became an exotic place, and was sometimes associated with revolution and liberty in continuation of what had been established by Mallet and his readers. Victor Hugo, Chateaubriand, Leconte de Lisle, Jules Verne, André Gide, Charles Cros, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Baudelaire or Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, long is the list of French writers of the nineteenth century that were at least partly attracted by the North.30 However, after the Franco-Prussian war of 1870/1, the North, Scandinavia and Norse mythology became more and more associated with the Teutonic and Germanic peoples and thereby to the newly established German Empire, pictured as a profoundly alien enemy. A utopian aspect, though, remained attached to the idea of the North, as for example in the reception of modern Scandinavian literature, such as the theater of Ibsen and Bjørnson; the mythology, however, became associated with Germany, mainly through the operas of Richard Wagner.

As mentioned above, comparative philology became the most important scientific paradigm when approaching Northern Europe, its literature, people, and mythology. The implicit idea of comparative philology was that language, literature, mythology, nature were different expressions of one and the same thing: a people. To put it shortly: “Swedish is a language is a culture is an origin is a nation is a land.”31 One could reconstruct the relation between different peoples through comparison between supposedly distinct languages, myths, cultures etc.

The royal library in Paris and the Société asiatique became important venues for the new science, and for what would become Nordic studies. The discursive proximity of Orientalism and Borealism finds here one of its foundations.32 The success of this approach was supported by the creation of new chairs at French universities specialized in the languages and literatures of the world, especially of Europe. However, the official title of these professorships already shows that philology was not the main focus of interest for the cultivated public. The chairs were entitled Littératures étrangères – foreign languages, and the professors’s task was to teach the literatures of foreign people, especially European. Two of these new chairs in Rennes and Strasbourg, were explicitly dedicated to the literature of the North; the literature of the North included in both cases English and German literature.33 The chair in Strasbourg was attributed to Frédéric-Guillaume Bergmann, a close friend of the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and a comparative philologist of the second generation. Bergmann studied at the centers of comparative philology in Göttingen, Berlin and Paris; he was one of the first to translate the Gylfagynning into French directly from the Old Norse,34 and he was certainly the most radical representative of the new paradigm of comparative philology, combining comparative linguistics with comparative literature, ethnology, and mythology.

Ampère was probably the first to give a public lecture on Old Norse literature at the Faculté des Lettres in Paris (1832), when he stood in for his famous teacher Claude Fauriel on one occasion. Fauriel was the first professor of foreign literatures in France who had specialized in the literature of the Mediterranean. His student Ampère turned his attention to the North, traveling through Germany and especially Scandinavia. What he knew about Scandinavian literature and Old Norse in particular, he had learned in Copenhagen from scholars such as Nyerup, Rafn, and Rask, as he reports in his well-written travelogue. In his published lecture, however, he rarely cites his sources. Ampère published many of his works in journals such as La Revue de deux mondes, and his work on Nordic literature and mythology is most easily accessible in his 1850 work Littérature, voyages & poésies.

The most influential scholarly writer on the North was without a doubt Xavier Marmier, who was appointed as professor of Foreign literature in Rennes the same year as Bergmann in Strasbourg. But while Bergmann rarely left his hometown, Marmier was already an experienced traveler. Among other things, Marmier had traveled to Germany and Scandinavia as part of the great French scientific expedition of the ship La Recherche, and had met virtually all the important Scandinavian intellectuals of the time, including Lars Laestadius, who introduced him to Sámi mythology. After only spending some months in Rennes, he left for another expedition to the North Pole. His travelogues, novels and essays on the Nordic countries were widely read and certainly a central source for every French language reader interested in the North, evoking the history and mythology of ancient Scandinavia as part of his contemporary experience of the sublime and rude landscape of the North.35 Marmier’s reception of Old Norse mythology was very much influenced by this aesthetic rather than scientific methodological approach; Cyrille François has therefore rightly called him a literary tourist.36

In spite of this burgeoning professionalization of the study of the North and Old Norse mythology, the field remained dominated by learned amateurs long into the twentieth century. Pierre-Brice Stahl’s list of translations and editions of the Poetic Edda in the present volume testify to this. However, much research has yet to be done. A fascinating, but largely unknown figure seems to have been the productive, probably Belgian intellectual Félix Wagner who published several scientifically valuable and well-commented translations of Old Norse literature. In any case, as a partial result of these scholarly endeavors—and the reception of German philologists—it was assumed at the end of the nineteenth century that the Old Norse mythology was an expression of the nations of the North, most often understood as Germanic, and as such nicely distinct from the French. Very few French language writers would see in the stories of Odin and Thor reflections of their own history, as it still was possible in the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century.

A similar tendency can be found in the literary field proper. As mentioned above, many nineteenth-century writers of importance like Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine or Arthur Rimbaud saw the North as a place of sublime hope and aesthetic renewal, featuring heroic seamen encountering Icebergs or the barbaric ignorance of school-aesthetics. It is important to note that only very few Scandinavian literary works were translated. Some translations were even rather unsatisfying like Esaias Tegnér’s Frithiof’s saga (1825), presented by Louis Léouzon Le Duc in 1850 in the first and only volume of his Histoire littéraire du Nord. The prose translation was accompanied by the translation of two other poems by Tegnér, but more importantly by a scholarly introduction to the work of Tegnér and a more than a hundred page- long dictionary of mostly Norse mythology. Léouzon Le Duc translated the Finnish Kalevala and Nicander’s Runeswärdet och den förste riddaren (The Runesword and the First Knight, 1820, transl. 1848). The foremost sources of knowledge were thus still travelogues, literary essays, often based on readings of German books, literary works and translations and, of course Mallet’s and others’ translations of the Eddas and sagas. The pre-Christian North was hence not only because of the public interest, but also because of lack of translations, the most accessible North. A significant exception from this rule seems to have been only the novels by feminist writer Frederika Bremer, which were devotedly translated by Rosalie Du Puget, who also translated the Edda.

In this sense, the early nineteenth-century writer François-René Vicomte de Chateaubriand includes the Eddas among “les productions les plus étrangères à nos mœurs, les livres sacrés des nations infidèles” [the most foreign productions to our morals, the sacred books of the infidel nations].37 These remarks are to be related to the main purpose of the work of Chateaubriand for whom “ce n’est que sous le christianisme qu’on a su peindre la nature dans sa vérité” [it is only under Christianity that one knew how to paint nature in its truth]. However, even if the men from the North are seen as barbarians, they are not necessarily portrayed in negative terms, apart from their religion. Chateaubriand concludes, for example, in the Analyse raisonnée de l’histoire de France: “Lorsque la Barbarie envahit la civilisation, elle la fertilise par sa vigueur et par sa jeunesse ; quand au contraire la civilisation envahit la barbarie, elle la laisse stérile” [When barbarism invades civilization, it fertilizes it by its vigor and youth. When, on the contrary, civilization invades barbarism, it leaves it sterile].38

The barbarian North with its foreign religion thus had a civilizing mission thanks to its youth and energy. This mytheme complex is inherited at least from Mallet and will only gain in attractiveness. Pierre Victor’s play Harald ou Les Scandinaves (Harald or the Scandinavians, 1825), dedicated to the king of Sweden and Norway and former French marshal is an interesting case in point, as is Jean-Marie Chopin’s Révolutions des peuples du Nord (1843):

du viiie au xie siècle, la Scandinavie remplit, à son insu, une mission civilisatrice ; d’une part, le principe d’activité auquel elle obéit, l’entraîne insensiblement dans le mouvement chrétien ; de l’autre, elle modifie les peuplades sauvages que les Saxons, convertis, refoulent au Nord et à l’Orient. Plus tard, cette influence se caractérise d’une manière plus nette : le christianisme vient donner un but, une âme à l’énergie barbare.39

[From the eighth to the eleventh century, Scandinavia fulfilled, unknowingly, a civilizing mission; on the one hand, the principle of activity to which it obeyed led it imperceptibly into the Christian movement; on the other hand, it modified the savage peoples that the converted Saxons drove back to the North and to the East. Later, this influence was characterized in a clearer way: Christianity gave a goal, a soul to barbarian energy].

Even though many French writers of the nineteenth century remained attached to the idea of a naturally Christian truth and consequently had an ambivalent relation to the pre-Christian North, they were clearly fascinated by the medieval North as the realm of rebirth and energy. Significantly, they often used the word “révolution” in this revolutionary century to describe the impact of the people of the North, even if of course a closer reading shows that the attached meaning was not always in tune with the language of political revolutionaries. Francesco Sangriso’s article on Charles Leconte de Lisle in the present volume analyses another significant case, as does Virgine Adam’s contribution on the representation of Norse Myth in French opera. The reception of the legends of the Nibelung in popular culture has yet to be studied in this sense, and Alexandre Dumas’ Les Aventures de Lydéric, grand-forestier de Flandre (The Adventures of Lyderic, great forester of Flanders,1841) would be a paradigmatic example. Often, these works tried to bridge the difference in beliefs by referring to the natural religion of the pagan people. For example, Pierre Victor explains in the commentary to his above mentioned play, that “Thor y figure comme la divinité principale, formant avec Odin et Freyr une trinité analogue à celle de notre religion”40 [Thor appears as the main deity, forming with Odin and Freyr a trinity similar to that of our religion].

Fig. 3: Joseph Thierry: Orfa, ballet, 1st act. Académie impériale de musique

© Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

As we have seen, the people of the North and their belief systems were perceived as different from the French, but not in profound opposition, not as something clearly distinct. At the end of the nineteenth century, especially in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war, this changed. When nationalism as a political ideology was vigorously promoted in the anti-Napoleonic wars of the early years of the century, for example in Fichte’s Addresses to the German Nation, the Franco-German opposition was a key element. It was enhanced by the ideas of comparative philology, which suggested a unity between people, place, language and myth and claimed that the German and Scandinavian people were related, Germanic brothers and sisters. The Nordic deities became associated to the concept of Germanic peoples and culture, and the Germanic people was thought of as synonymous to Germany. When after the Franco-Prussian War the German Empire was founded, this association became seemingly natural and was used until the Second World War, especially in nationalist and nationalist-inspired circles.

Odin and Thor became effective tools in anti-Germanic propaganda to portray the “vieux Bon Dieu” [good old God] of the Germans or, more precisely, of Kaiser Wilhelm II. In order to differentiate France from Germany, several postcards and press articles associated the Nordic deities with the Kaiser—in opposition to the French that were represented as followers of the Christian God in its Catholic variant. Nordic mythology was to become one of the motifs for representing or describing the invader. The right-wing intellectual and member of the Académie française, Maurice Barrès, for example, referred in Chronique de la Grande Guerre (Chronicle of the Great War, 1815) to the realm of the Nordic gods: “Les envahisseurs arrivent avec leurs héros et leurs dieux. C’est Luther, et plus loin tout le Valhalla qui accourent” [The invaders arrive with their heroes and their gods. It is Luther, and further on all Valhalla who rush to the front.].41

One of the best-known representations of Norse mythology from this war represents Thor as an allegorical personification of Germanic barbarism destroying Gothic monuments.42 This illustration is based on one of the emblematic quotations used by the anti-German propaganda of the First World War:

Alors, et ce jour, hélas ! viendra, les vieilles divinités guerrières se lèveront de leurs tombeaux fabuleux, essuieront de leurs yeux la poussière séculaire ; Thor se dressera avec son marteau gigantesque et démolira les cathédrales gothiques.

[Then, and that day, alas! will come, the old warrior divinities will rise from their fabulous tombs and wipe the secular dust from their eyes; Thor will rise with his gigantic hammer and destroy the Gothic cathedrals]

This exclamation comes originally from the German poet Heinrich Heine and was published in 1834 in the Revue des Deux-Mondes, of course in a very different context.43 In the history of its French nationalistic reception, the text was presented as a prophetic announcement and was used by many artists, writers and journalists.44 Nonetheless, during the First World War, Nordic mythology remained one of the many motifs used to describe or illustrate the conflict, alongside figures such as Attila, Death, Luther, but also the Huns, the Vandals and the Goths. It was above all part of a broader discourse of otherness opposing “civilization” and “barbarism”.

After the First World War, there was hardly any room for an alternative use of Nordic mythology. When Nordic gods and heroes were cited in French literature and art, they remained associated with the German enemy, even if scholars like Maurice Cahen sought to differentiate Scandinavia from Germany.45 Others, such as Georges Dumézil, propagated, not without sympathy, the idea that a living and authentic Germanic mythology was at the origin of Nazi Germany’s success:

Le troisième Reich n’a pas eu à créer ses mythes fondamentaux : peut-être au contraire est-ce la mythologie germanique, ressuscitée au xixe siècle, qui a donné sa forme, son esprit, ses institutions à une Allemagne que des malheurs sans précédent rendaient merveilleusement malléable ; peut-être est-ce parce qu’il avait d’abord souffert dans des tranchées que hantait le fantôme de Siegfried qu’Adolf Hitler a pu concevoir, forger, pratiquer une Souveraineté telle qu’aucun chef germain n’en a connue depuis le règne fabuleux d’Odhinn.46

[The Third Reich did not have to create its fundamental myths: perhaps, on the contrary, it is Germanic mythology, resuscitated in the 19th century, which gave its form, its spirit, its institutions to a Germany that previous misfortunes made marvelously malleable; perhaps it is because he had first suffered in the trenches haunted by the ghost of Siegfried that Adolf Hitler was able to conceive, forge, practice a Sovereignty such as no German leader had known since the fabulous reign of Odhinn.]47

The Short Twentieth Century and a Glimpse into the Twenty-first

The association between Germany and Germanic/Nordic mythology slowly declined in the second half of the twentieth century. It would take some time before Old Norse mythology was reused in French literature, art and popular culture. A known example is the comic book Astérix et les Normands (Asterix and the Normans, 1966) by Uderzo and Goscinny. The Norsemen depicted swear to their gods in the humorous way typical of the series (“Par Thor ! ; Par Odin !… Par exemple !” [By Thor!; By Odin!… By/For example]).48 However, the narrator presents the gods of the North as gods of war in the tradition of the first half of the twentieth century:

Ils ont des dieux terribles, les Normands : Thor, le dieu de la guerre, qui ne se réjouit que dans le feu et le sang, et Odin, qui accueille dans un grand banquet, les guerriers morts au combat.49

[They have terrible gods, the Normans: Thor, the god of war, who rejoices only in fire and blood, and Odin, who welcomes in a great banquet, the warriors killed in battle.]

The official English translation moderates this presentation; perhaps because the national mythologies in Great Britain and the United States often promote a closer relationship to the Vikings: “They worship Thor, the god of war, and Odin, who invites warriors slain in battle to feast with him in Valhalla…” In spite of their violent, rather bloody disposition, these Northmen did not come to the village for raids, and this is the occasion for René Goscinny to play with the apparent anachronism of the encounter with Asterix by having them declare: “Nous ne sommes pas venus faire la guerre. Pour ça, nos descendants s’en chargeront dans quelques siècles” (“We did not come to make war. Our descendants will take care of that in a few centuries”).50

A significantly more important independent reception of Old Norse Mythology is the Belgian comic series Thorgal by Jean Van Hamme (script) and Grzegorz Rosiński (drawing), which has been narrating since 1977/1980 the destiny of an intergalactic orphan in the universe of the Vikings. 38 volumes have been published so far, and with Les Mondes de Thorgal, there is even a spin-off series with side stories, often featuring minor characters. The mythological cosmography and mythology of the North inspire the plot in many details. Even if war and conflict have an important place in the series, it is much about avoiding violence, the search for origins and living one’s life in accordance with nature’s laws. Besides these albums, a computer game and novels have been released.

When the warriors from the North appear for a second time in Asterix in the 1975 comic book La Grande Traversée (Asterix and the Great Crossing), they are no longer called “Norman,” even though “Norman” has remained the most common term to describe the people of the North. Indeed, as Yves Gaulupeau has shown, the term Norman dominated for example school textbooks until the second half of the twentieth century.51 The term Viking becames more frequent only by the end of the century, progressively replacing the term “Norman”. Consequently, the 2006 French-Danish adaptation of the book Asterix and the Normans was called Asterix et les Vikings (Asterix and the Vikings).

It is not unlikely that the term Viking found its entrance into French culture through British and American media that found an important audience and thereby replaced the nationalist Germanic interpretation that had dominated the period before with a different discourse, connected to the Anglo-Saxon world. We can think of film productions like The Vikings (1958) and The Long Ships (1964), American comic strip Hägar the Horrible by Dik Browne, translated into French under the title Hägar Dünor (a French pun on the expression “du Nord”). Later, Tolkien and the Fantasy universe that developed in his wake had a significant impact, as well as of the reception of Viking metal from the middle of the 1980s on, as is shown by Simon Théodore in the present volume. This last point is not just a matter of reception: according to the Metal Archives database (www.metal-archives.com), there were and are many active French Viking-metal bands.

We do not have to discuss here the reception of the many television series, Thor in the Marvel universe, the entrance of Vikings into the world of Computer games and the many other international media success stories, as it is similar to their reception elsewhere in Europe. It should, however, be mentioned that the French video game publisher Ubisoft released in 2020 as the twelfth part of its Assassin’s Creed series Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, which is based in a Viking world and consequently incorporates many elements from Norse mythology into its narrative.

Lastly, we have to mention briefly Japanese Manga and Anime productions, which have found a broad readership in France and Belgium with their developed comic book and graphic novel culture. For instance, the anime adaptation of the manga The Knights of the Zodiac (聖闘士星矢 Seintō Seiya) adds a narrative arch, not found in the original manga, entitled Asgard, where Odin’s divine warriors including Siegfried of Dubhe, Thor of Phecda and Freyja of Polaris battle for a better life. As a complement, we can mention the series Ah! My Goddess (ああっ女神さまっ, Aa! Megami-sama!) by Kōsuke Fujishima published in French by Manga Player (1997-1999) and then by Pika Edition in 48 volumes (2000-2019) and which is based on the Nordic mythology.

All these productions have participated in a restructuring of the social knowledge about Vikings and Norse mythology. As suggested above, the reference to Vikings has largely replaced other references. Except for right wing and conservative circles, very few French readers, spectators and gamers will associate them with Germany, the Germanic people and the conflicts of the nineteenth and the twentieth century. They have become again the vectors of a youthful utopian culture as in the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century, reproducing and readapting many mythemes and aesthetic choices from this period. When Neil Gaiman’s successful Norse Mythology was translated into French, the French publisher decided to call it Mythologie Viking (2017). Old Norse mythology appears in many circles to be detached from questions of ethnic origin and open to at least European adaptation. French comic books like Beowulf (2008), Aslak (6 vol., 2011-2019), Asgard (2 vol., 2012-2013), Saga Valta (3 vol., 2011-2017), Walhalla (3 vol., 2013-2018) and L’exilé (2020) are but some examples. They do not even consider the question of whether it is legitimate for a French or Belgian artist to use these narrative universes but use them naturally to attract their public.

Besides these artistic appropriations, we must also mention the impact of a prolific academic writer, Régis Boyer, who has become the main popularizer and expert for the French public of Norse mythology.52 Today, however, his work is facing competition from the French language YouTube channel Nota Bene, which currently has 1.78 million subscribers. Benjamin Brillaud, the creator of this history channel, has published several videos on Norse mythology and authored a comic book La mythologie nordique (2020). Both the book and the channel were created in close collaboration with academic scholars.

As this very hasty and far too brief overview of the French history of the reception of Norse mythology has shown, it is indeed a very rich and fascinating history that invites further research. Many sources seem to be still waiting for a thorough study, many actors need to be explored and contextualized. Some elements seem to be in urgent need of more detailed study, such as the French-language reception of Norse history and mythology in Nordic aristocratic milieus, the plays, ballets, and operas from the nineteenth century, the poems and novels from French Normandy, Brittany or Alsace that evoke local history, or the comic scene that we mentioned a few paragraphs above. The use of Norse mythology in right wing and conservative circles as well as by neopagan groups is, in spite of some endeavors, another important research lacuna. Many other aspects can be found in the articles that we present here, particularly the research report from an international research program given by Alban Gautier, Alain Dierkens, Odile Parsis-Barubé and Alexis Wilkin. Many hypotheses proposed here might be reconsidered through detailed case studies. If this is the case, we will be grateful to its authors.

A last word before leaving this all too long introduction: we wish to express our warmest thanks to all the contributors to the volume, to the new editors of Deshima, Cyrille François and Roberto Dagnino, for their patience and support, to Ersie Leria for the careful editing and layout, and the team from the Presses universitaires de Strasbourg for their long standing confidence in our publication projects.